In the mid 1960s, a tide of anger began to swell at what was then called San Francisco State College. Students had a litany of complaints -- the Vietnam War, the ROTC's presence on campus, and the college's practice of providing students' academic standing to the Selective Service. Even the price and quality of food in the cafeteria came under attack.

But two things incensed students more than anything else: admissions practices that mostly excluded nonwhites from entering SF State, and the curriculum, which students of color viewed as largely irrelevant to their lives.

On Nov. 6, 1968, exactly four decades ago this fall, the dam broke. Protesting students, led by the Black Students Union and a coalition known as the Third World Liberation Front, barged into one classroom after another and announced that a strike was on and class was dismissed.

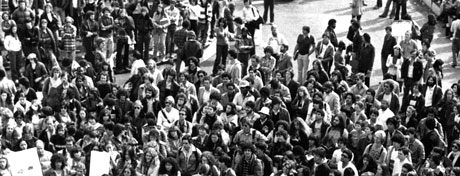

Through that fall semester and into the spring, huge throngs of demonstrators, mostly students but also faculty, staff and community members, rallied on campus, raising clenched fists and chanting "On strike! Shut it down!" Classes were cancelled. Powerless to quell the uproar, the administration essentially ceded control of the campus to the San Francisco Police Department, whose baton-swinging tactical squad injured scores of protesters and arrested hundreds. The conflict played out on TV screens in living rooms across the country, shocking a nation incredulous at the level of conflict.

Out of the strikers' determined efforts during those five months -- still today the longest student-led strike in the history of American higher education -- would emerge a university committed first and foremost to equity and social justice -- a radical notion then and even now.

"It's the pedagogy of liberation and it basically argues that a public education has to be first and foremost about the public good. But this is not typical for most public institutions," says Kenneth P. Monteiro, dean of the College of Ethnic Studies, established in 1969 as one of the strikers' non-negotiable demands. "A lot of universities pay lip service to it, but it's very unusual for a university to put out a [strategic plan] stating that its number one goal is equity and social justice."

On the eve of its 40th birthday, the College of Ethnic Studies is stronger and more influential than ever, defying critics who said it would not survive a decade. Per-semester class enrollment in the college started at approximately 200 and now exceeds 6,000. The original complement of 10 instructors has grown to 50 tenure and tenure-track faculty.

The college upended the singular dominance of the white-centric model of teaching by offering new departments -- among them the nation's first-ever black studies program -- and new courses that exposed students of color to their own histories, cultures, heritages and contributions, broadening the range of intellectual tradition available to all students. "What we were asking for was that the institution be more sensitive to the intellectual needs of oppressed people whose voices were not being heard," says Professor of Raza studies Roberto Rivera (B.A., '65), then a young instructor who risked his nascent academic career by joining the strikers and getting arrested.

In coming years, universities across the country would follow SF State's lead by embracing curricula that spoke to peoples of color, the marginalized and the dispossessed. Black studies, Native American studies, Asian American studies, women's studies and gay and lesbian studies -- then practically unheard of at college campuses but now ubiquitous -- can all be traced to that period of unrest at SF State. While the College of Ethnic Studies has been widely borrowed from, it has never been duplicated. It remains the only such college in the United States.

President Robert A. Corrigan, in the 1960s a faculty member in American Studies at the University of Iowa, was among those watching the conflict unfold at the college on the West coast. His campus was profoundly influenced by the "extraordinary movement spreading out from SF State across America" and Corrigan was asked to establish the first black studies program at the University of Iowa. Within a decade of the strike's end, more than 430 other U.S. colleges and universities would also offer ethnic studies programs and courses.

"The student-led strike of 1968 at San Francisco State changed this campus and opened doors to not only students and faculty of color but to a broad range of men and women who had been excluded or overlooked in higher education," President Corrigan says. "Forty years later we look back on a time of strife and sacrifice to say unequivocally that fundamental changes to higher education have resulted."

SF State's student body, largely white and middle class in the 1960s, is now a vibrant mix of race, ethnicity, political bent, income level and nationality. More than 70 percent of State's 30,000 students are members of racial or ethnic minorities and an increasing number of its white students come from the working class.

Many of the current students -- or even their faculty -- might never have seen the inside of a university classroom had not SF State protesters pushed for a special admissions program for underrepresented students of color and those from disadvantaged backgrounds. What came to be known as the Educational Opportunity Program (EOP), co-founded by SF State's then-dean of undergraduate studies, African-American psychologist Joseph L. White, would, within just a few years, become institutionalized at each CSU campus. At SF State alone, more than 15,000 alumni -- many the first in their families to attend college -- hold degrees today due in no small measure to EOP.

"If Kent State was the paradigm shift for the antiwar movement and Berkeley for the free speech movement, it's not an exaggeration to say that San Francisco State cracked the paradigm for diversity in the student body and the curriculum," Monteiro says. "This was the epicenter."

What is sometimes lost in the discussion of the strike are the penalties paid by arrested strikers, particularly those who led the charge. Nesbit Crutchfield (attended '67-'71; '74), now a mental health administrator in Oakland, did 16 months in jail and earned a criminal record "that follows me around to this day." Hari Dillon (B.A., '71), president of the Vanguard Foundation, a civil rights organization in San Francisco, spent nearly a year behind bars. John Levin (attended '66-'68), a Bay Area playwright, about six months.

Many strikers rose to prominence in fields from law to public service. Ronald Quidachay (B.A., '70) would become a San Francisco Superior Court judge. Danny Glover (attended '67-'72) went on to worldwide fame as an actor and activist.

Like Rivera, a number of strikers, perhaps ironically, would settle into careers at the very institution that had been the target of their wrath. Laureen Chew (B.A., '70) is associate dean of the College of Ethnic Studies. Danilo Begonia (B.A., '69; M.A., '70) is a professor of Asian American studies, Dan Gonzales (B.A., '74), an associate professor of Asian American studies, Margaret Leahy (B.A., '71), a lecturer in international relations, and Eric Solomon, a professor emeritus of English.

Even after the long passage of time, memories of the strike remain fresh.

"I can still feel all that pushing and screaming. I saw my friend get his head bashed and another person trampled," recalls Chew of the day she was arrested and taken to the Hall of Justice downtown, where she was herded into a room with scores if not hundreds of fellow strikers.

"Once we got there, it was crazy. People were screaming, 'On strike! On strike! Shut it down!' People were screaming so loudly that you could feel the building shake. Then somebody shot a gun in the air just to get us to shut up, and the next thing I knew, there was a high-pressure hose and I was swept from my chair against a wall."

Chew, taken into custody during the mass arrest of Jan. 23, 1969, would do 20 days jail time in San Francisco and San Bruno.

To understand why the strikers were so angry (they addressed the short-tenured Robert Smith as "President Pig" -- to his face) and why they would risk so much, it is necessary to step back in time half a century. The San Francisco of the 1950s and '60s was not yet the city known today as a bastion of tolerance and liberal thought.

"We didn't have George Wallace standing at the door. We didn't have legal segregation. We had institutionalized racism, which is just as pernicious and even more insidious," Dillon says.

Good jobs went to whites. Blacks, many displaced from the shipyards by returned war veterans, were relegated to work as domestics, shoe shine men and postal workers. Downtown professional clubs barred nonwhites and racially restrictive covenants kept Jews and minorities out of neighborhoods, including some adjacent to SF State.

Public universities "by policy or practice, were not very inclusive of nonwhite and poor students, even in a place like California," Monteiro says. Educational paths were largely preordained according to the color of one's skin and station in life: Elite whites went to the University of California or private schools, middle class whites went to a California State College, and others went to a junior college, if they went to college at all.

"That was one of the things that really bothered me," Judge Quidachay recalls. "The state had a master plan, and everybody had to go down a particular path, either a JC or a trade school, or a state college or the university. My feeling was, hey, let's open this up."

One of the main catalysts of the strike was the firing of George Mason Murray, an African-American instructor of English and Black Panther Party member whose alleged incendiary rhetoric included calls for black students to arm themselves on campus as protection against "racist" administrators.

At its core, the strike was about "liberation," Dillon says. "Our organizations were the Black Students Union and the Third World Liberation Front -- and that was our goal -- liberation. Liberation from a social environment where racism had previously prevailed; an environment we had suffered under for too long -- an environment we were determined to change for our children and grandchildren."

Along with its legacy of accomplishment, the strike has left bitterness for some, half-fulfilled hopes for others. Even four decades later, emotions among faculty members who were in opposing camps during the strike run so high that some among them still do not speak to each other. In the settlement that officially ended the strike, the Black Students Union lost key demands. Notable among them were full autonomy over faculty hiring and retention in the Black Studies Department, and the reinstatement of Murray and Nathan Hare, the influential African-American sociologist whom S.I. Hayakawa, the last of three strike-era presidents, fired as the first chairman of the newly formed Black Studies Department.

Yet Crutchfield says that if he could go back in time, he would do it all again, even knowing that most of the current crop of college students, at SF State or anywhere else, probably do not appreciate his sacrifice, if they are aware of it at all.

"What's important to me is not whether my sacrifice is appreciated," says Crutchfield. "What's important to me is that because of my sacrifice, many, many young people, many people throughout this state and nation, and the world, are seen now as whole people, as people who have the ability to excel, as people who should be evaluated based on their worth rather than on something as arbitrary as their race or background."