For California Academy of Sciences Field Associate Ray Bandar, art is in his bones

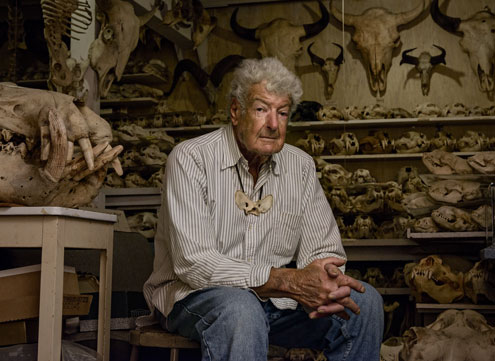

Ray Bandar picked up his first skull in 1953 at Baker Beach. He has since amassed a museum-worthy collection of more than 7,000 specimens. Photo by Ross Feighery

“Call me Bones.” Ray Bandar(A.B., ’55; Cred., ’58) invites the use of his nickname at first meetings, and it’s a convenient shortcut to the topic that has dominated his life. The San Francisco native’s extreme exploits in bone collecting have been documented in numerous media outlets including National Geographic and NPR, and last year he curated a 10-case display for “Skulls,” the major California Academy of Sciences exhibit, which featured more than 700 titular specimens from his collection.

Yet step into his Diamond Heights home, which houses his storied collection across three levels, and it’s the art that first overwhelms the senses, with paintings, drawings, masks and sculptures covering every inch of the living room from floor to ceiling. Among the artworks, animal bones have been carefully placed as part of the display. This artist’s perspective — along with passions for biology and education — has propelled the San Francisco native’s lifelong penchant for collecting.

It’s a life story Bones Bandar tells in nicknames. In grammar school, with his wild mop of hair and a love of climbing trees, “They called me Tarzan.” As a young man showing off his swimmer’s physique on Ocean Beach, “They called me Shoulders.” In addition to his impressive boyhood nature collections (“They called me Reptile Ray”), which he submitted to the nearby Steinhardt Aquarium, Bandar showed early artistic talent. After a peacetime Army stint, he used the GI Bill to attend the Academy of Art, where he met his wife, Alkmene, a Napa native and talented artist herself. He moved on to what’s now California College of the Arts, but decided commercial art wasn’t for him.

Eventually, the lifelong nature-lover chose to focus on teaching biology and headed to SF State, where he finished his bachelor’s degree in art, minored in science and earned his teaching credential. It was a turning point. Biology Professor Joel Gustafson piqued his interest in entomology and, more importantly, forged a connection with the Cal Academy that would last a lifetime and ultimately benefit generations of students and museumgoers.

One afternoon in 1956, Gustafson sent Bandar down to the Academy for a job interview. Bandar didn’t help his own cause: He had no time to get a haircut or change out of his field-collection wardrobe of combat boots, patched jeans and a tattered shirt. “I looked like a hobo,” he remembers with a laugh. But then-director Robert C. Miller saw Bandar’s genuine passion shine through. The two bantered about his interests in reptiles, insects and mammals, recalls Bandar, “And suddenly Miller says, ‘You’re hired!’ just like that.”

Bandar spent weekends showing school children around the Academy, and, of course, he participated in collection expeditions. After he earned his teaching credential in 1958, he gave the Academy his resignation in anticipation of his new full-time vocation. But Miller wasn’t interested in losing one of his most dedicated collectors. Bandar was given the title of field associate and sent on paid collection excursions, including to Mexico and Australia. He still holds that title today.

“Ray Bandar is an extraordinary friend to the California Academy of Sciences,” says Meg Lowman, chief of science and sustainability at Cal Academy, which will one day receive his entire collection. “The skulls and skeletons Ray has collected will help make the world a better place through their applications to research, exhibits and education activities at the Academy and beyond.”

Bandar’s role as an educator expanded the dimensions of his collecting. “When I knew I was going to teach biology, I wanted to get as many different kinds of skulls from as many different animals as I could,” he says. He taught biology for 32 years at Oakland’s Fremont High School and relished the way bones and dissections engaged his students. He still hears from many students he inspired, and he’s particularly proud of a beetle he collected in Baja California that a former student, now a Ph.D. biologist, named after him: Inyodectes bandari.

Now 88, Bandar doesn’t collect anymore — he walks slowly and has balance and breathing problems not unusual for his age. But he still curates an annual Halloween exhibit and other occasional displays. Sitting in his workshop among trays of painstakingly prepared bones commingled with his wife’s drawings and paintings, he contemplates one last nickname. Would it be “Artist,” “Teacher” or “Scientist”?

“Being affiliated with the Academy, there’s a lot they want to know about science — disease, trauma and other details,” he says. “But for my own taste, I look at a piece and I think, ‘Oh, what a magnificent piece of sculpture.’”