|

| |||

Speaking Volumes

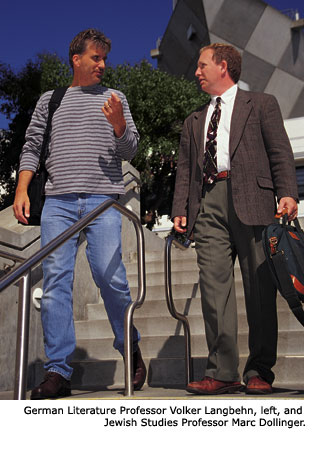

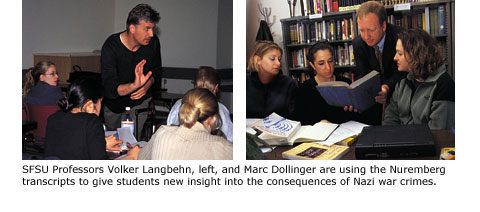

The caller, Amy Rabbino, told Dollinger that she worked for a philanthropist who recently had come into possession of a complete set of original transcripts from the first Nuremberg trial. The philanthropist, George Sarlo, was looking for a library that could put them to good use, Rabbino said. Was San Francisco State interested? Dollinger, who is a scholar of American Jewish history, had never actually seen the original transcripts. But he knew immediately that what Sarlo was offering the University was an original set of one of the most important primary source documents of the 20th century. The 42 hardbound volumes, published by the U.S. Government Printing Office between 1947 and 1949, are a verbatim account of the trial of high-ranking Nazi officials before the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg, Germany, from November 1945 to October 1946. The text is mostly in German, with some French and English. Dollinger didn't have to ponder Rabbino's question long. As the first holder of the University's Richard and Rhoda Goldman Chair in Jewish Studies and Social Responsibility, he is deeply involved in San Francisco State's efforts to develop its Jewish Studies Program into a vibrant and comprehensive center for learning, teaching and community service. The transcripts, Dollinger thought, would be an invaluable teaching and research tool and a feather in the cap of SFSU's Marvin L. Silverman Jewish Studies Reading Room, which already has a collection of more than 2,000 academic, reference and historical books on Jewish subjects. "Yes, yes, yes!" Dollinger shouted into the phone. "Where can I drive right now to pick them up?" Rabbino told Dollinger to sit tight; she'd drive them to campus herself. When she arrived, Dollinger and Chaim Mahgel-Friedman, the administrative office coordinator for the Jewish Studies Program, were waiting for her in the parking lot. The two men loaded four, hefty cardboard boxes onto hand trucks and wheeled them up to Dollinger's office on the fourth floor of the Humanities building. Unable to read German, Dollinger knew that the text would mean little to him without a translator. He called Volker Langbehn, a German-born literature professor whom he knew only casually but whose office is located three doors from his own. Langbehn promised to come over as soon as he could.

The two professors -- too impatient to look for scissors -- fumbled to open the packing tape on the boxes with their office keys. The seals finally broken, each picked a volume at random and gingerly lifted it out. The pages were yellowed and the paper jackets so brittle that tiny pieces fell in flakes to the floor. Titled the "Trial of the Major War Criminals Before the International Military Tribunal," the volumes are known as the "Blue Series" because of their indigo covers. Of the many original sets, more than 650 are held in libraries today, 45 of them in California, according to Leslie Kane, executive director of the Holocaust Center of Northern California. The transcripts are available on CD-ROM and online at Yale Law School's Avalon Project and other Web sites. About half of the 42 volumes contain testimony from the 11-month trial of 22 Nazi officials whom the victorious allies -- the United States, Great Britain, France and Russia -- indicted at the end of World War II on war crimes and other charges for the systematic murder of millions of Jews, gypsies and others, as well as for planning and carrying out the war in Europe. Remaining volumes contain thousands of documents submitted as evidence. The text offers a chilling history lesson and a brilliant illustration of what political theorist Hannah Arendt called "the banality of evil," Langbehn said. Hermann Goering, Hitler's designated successor, reflects unapologetically on the need for the concentration camps so that order could be preserved. A camp survivor named Marie Claude Vallant-Couturier recalled a Nazi orchestra playing sprightly tunes as soldiers separated those destined for slave labor from those to be gassed. SS General Otto Ohlendorf talked of lining up men, women and children along a tank ditch so that they could be executed by firing squad. "This is the most detailed chronology we have of the Nazi atrocities -- tens of thousands of pages of personal history," Dollinger said. "It's a very complete picture of the most horrific moment in modern Jewish history." Though 11 other trials involving more than 100 defendants took place at Nuremberg in the post-War years, by far the most attention has focused on this first trial, not surprisingly, given the notoriety of the defendants. In addition to Goering, they included Rudolph Hess, Hitler's deputy, and Albert Speer, minister of armaments and war production. Of the 21 defendants who sat in the dock (Martin Bormann was indicted in absentia and never found), 11 were sentenced to death by hanging, three were acquitted and the rest sentenced to prison. More than punishment for Nazi leaders, the Nuremberg trials enshrined in international law the principles that individuals must be held accountable for waging war and crimes that shock the conscience of humanity, and that there is no validity to the defense that one was merely following orders. The United Nations ad hoc tribunals for Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia stand on these principles, as did the case against Chilean dictator Gen. Augosto Pinochet and likely would a tribunal for Iraq's deposed leaders -- should one come to pass.

Langbehn's specialty is 18th-20th century German literature, with a focus on post-War writings. Several years ago, he had incorporated transcripts from the first Nuremberg trial into a course he taught at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, on the representation of the Holocaust in German media. But as the two professors talked, Dollinger found out that Langbehn's interest in the Holocaust reached far beyond the academic. Langbehn's father, Dollinger learned, had been a grunt soldier in the Nazi army during the War. As a teenager struggling with the shame of his country's genocidal past, the younger Langbehn had a difficult time dealing with his father's wartime service -- despite the elder Langbehn's insistence that he knew nothing at the time of what was happening in the camps. "At one point, we had very little to say to each other," recalled Langbehn, now reconciled with his father, who is 81. In his early 20s, ensconced in the soul-searching that gripped the country's collective conscience in the 1970s and 1980s, Langbehn declared himself a conscientious objector and opted out of military service. As allowed under law, he spent two years in alternative service with a German organization called Action Reconciliation Service for Peace. The group sends young Germans to communities to promote healing and reconciliation with those affected by the Nazi regime. Langbehn's tour of duty included restoration work at the Auschwitz and Mauthausen camps and a stint teaching kindergarten in Boston. Though he had come to the United States to work for peace, some "It was a tough time," said Langbehn. "Germans [in the early 1980s] were associated with being little Nazis, regardless of their age." Dollinger, who is Jewish, listened empathetically to Langbehn's story. As he did, he realized that what was happening in his office that afternoon went way beyond two academics getting excited about musty old books. A Jew and the son of a Nazi soldier had come together to grieve and reflect on the horrors perpetrated by the people of one against those of the other. It seemed a long way to have come in what is -- historically speaking -- a blip of time since the Holocaust. "To me it was just so optimistic and hopeful that the course of history had brought us together in a time and place where we could not only not hate each other, but actually be friendly and teach each other and share through common experience," said Dollinger, a fifth generation San Franciscan who earned his master's and doctorate degrees at UCLA.

Clay-Thompson doesn't know how the books got in the attic and family members who could shed light on the question have passed away. She conjectures they belonged to a friend of her parents who worked for the War Department as legal counsel for the U.S. government during the Nuremberg trials. "But why he would have brought them to us is kind of bizarre," Clay-Thompson said. "Since he lived in the Washington area, I would think he would have kept them in his own library." Wanting to find a good home for the transcripts, Clay-Thompson mentioned her unusual discovery Gray immediately offered to help. He called his friend and fellow human rights activist Sarlo, 65, president of the Sarlo Foundation in San Francisco. Sarlo and his wife, Kim, a San Francisco State graduate, established the foundation in 1992 to fund groups working in the areas of human rights, education, immigrant issues, and medical crisis intervention. More importantly, Sarlo is a Holocaust survivor. As a youngster in Nazi-controlled Hungary, Sarlo, his sister and mother escaped the Holocaust thanks to the heroic efforts of an Italian meat broker named Giorgio Perlasca. Passing himself off as the Spanish consul in Budapest, Perlasca saved the lives of thousands of Hungarian Jews by issuing them fake papers. Sarlo's father and most of his other relatives had already been rounded up by the Nazis and did not survive. Sarlo told Gray he would be happy to find a home for the transcripts. Two places that came to mind -- Stanford University and the Holocaust Center of Northern California -- already owned sets. Sarlo next thought of San Francisco State, where he had heard good things about the Jewish Studies Program. Just last year, the program established a new major in Modern Jewish Studies. The first baccalaureate recipients graduated in May. In addition to expanded offerings, the program actively promotes constructive dialogue between pro-Israel and pro-Palestine students. San Francisco State, Sarlo thought, might be just the place for a set of historical documents that make such a powerful statement about the horrible consequences of hatred and fear. He asked Rabbino, the program officer for the Sarlo Foundation, to get in touch with Dollinger. Today, the 42 volumes line the top shelf of a metal bookcase in the Jewish Studies Reading Room. Though the volumes have yet to be translated, Dollinger and Langbehn are flush with excitement about the possibilities they present: a rich trove of primary source material for graduate students and scholars; cross-listed courses in Jewish studies and German literature; and reading assignments for courses in history, psychology, and many other disciplines. Sarlo is pleased that the volumes are finally being put to good use after their long hiatus in the attic. He said it's important that young people look at the transcripts because they make the Holocaust real in a way that history books and even movies don't. If people don't know about it, he said, it can happen again. -- Anne Burke | ||||

Professor Marc Dollinger was sitting at his office desk, thoroughly absorbed in preparing lecture notes for his next class, when he got a telephone call that almost made him fall out of his chair.

Professor Marc Dollinger was sitting at his office desk, thoroughly absorbed in preparing lecture notes for his next class, when he got a telephone call that almost made him fall out of his chair.

That afternoon in Dollinger's office, Langbehn flipped through a volume, translating the text into English for his colleague's benefit. As he read aloud, Langbehn added bits of his own knowledge about some of the lesser-known defendants -- who they were and what roles they played in the Third Reich.

That afternoon in Dollinger's office, Langbehn flipped through a volume, translating the text into English for his colleague's benefit. As he read aloud, Langbehn added bits of his own knowledge about some of the lesser-known defendants -- who they were and what roles they played in the Third Reich. The volumes that Dollinger and Langbehn held in their hands have a slight air of mystery about them. Carmel Clay-Thompson, who lives in Virginia and works in Washington, D.C., as deputy director of the U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement, found the books underneath insulation in the attic of her parent's summer home in rural Fauquier County, Va.

The volumes that Dollinger and Langbehn held in their hands have a slight air of mystery about them. Carmel Clay-Thompson, who lives in Virginia and works in Washington, D.C., as deputy director of the U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement, found the books underneath insulation in the attic of her parent's summer home in rural Fauquier County, Va.