Four decades after finding his voice in San Francisco and a safe haven at SF State, Cleve Jones continues to stand up for social justice

By Rob Waters

THERE’S A PHOTOGRAPH on the wall inside Harvey’s restaurant on Castro and 18th Street that Cleve Jones (attended, ’77-’84) likes to show visitors. It was taken the night of Oct. 11, 1978. San Francisco Supervisor Harvey Milk, California’s first openly gay elected official, had debated State Senator John Briggs in Walnut Creek that night on Briggs’ now-infamous ballot measure to bar gay teachers from working in California schools.

Jones, then a San Francisco State student on the night of his 24th birthday, was working as an intern for Milk, his mentor. There was no room in the car taking Milk to Walnut Creek, so Jones had to stay in San Francisco and watch the debate on TV. Afterwards, he went off “in a bit of a sulk” to have a drink by himself. When Milk showed up at the bar with a donut and candle, a photographer immortalized the moment: Milk and two friends celebrating with a young, baby-faced Jones, who grins behind oversized glasses, a “No on 6” button pinned to his jeans.

One month later, they celebrated the Briggs initiative’s defeat. But the exhilaration of that victory wouldn’t last. Within three weeks, Milk and Mayor George Moscone had been assassinated at City Hall by ex-cop and ex-Supervisor Dan White.

Jones saw Milk’s body sprawled on the floor, this man “who saw value in me before any other person did, who loved me and raised me up, and I said to myself, ‘It’s all over. The movement’s done. He was our leader and he’s dead.’”

Later that night, 30,000 people gathered at Castro and Market streets and marched by candlelight to honor their deaths. And Jones knew it wasn’t over after all.

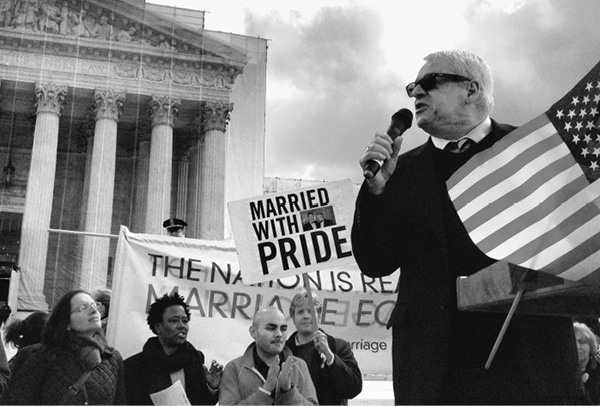

In the decades after the killings, Jones emerged as a leader in his own right, an activist “who belongs in the pantheon of heroic gay civil rights leaders,” in the words of former San Francisco Mayor Art Agnos. But there would be many more deaths to come, as AIDS enacted its horrific toll, along with heroic efforts to provide mutual support and push for research and treatment.

Today, of the four people in that photograph on the wall of Harvey’s, only Jones is still alive.

Jones enrolled at San Francisco State, which “had resources that were quite unusual and made it inviting for somebody like me. Today queer studies or gender studies are a given on campuses. But that wasn’t always the case, and SF State was a pioneer.”

It was also comfortable. “On the street then there was a lot of random homophobic violence,” he says. “But not at State — it was a very safe place for gay people to go.”

He joined the gay student union and took urban studies with Professor Emerita of Political Science Kay Lawson, feminist theory with Professor Emerita of Women Studies Mina Caulfield, and “Variations in Human Sexuality” with John DeCecco, an out gay professor who is now retired. Most importantly, Jones learned the skills of political organizing.

As the campaign against the Briggs initiative heated up, he rode Greyhound buses to campuses across the state and recruited fellow students at SF State to join the fight. Almost none of them are still alive today, Jones says.

Glimpses of Jones’ journey, by turns glorious, funny and agonizing, fill his 2016 memoir When We Rise, which helped inspire the television miniseries of the same name. The series, broadcast on ABC in February and March, dramatized the story of San Francisco’s gay rights movement, thrusting Jones and other real-life activists into the spotlight. It’s a place Jones is happy enough going—though he does have his complaints.

“Who knew I had so many exes still alive?” says Jones, sounding cranky, over lunch at the Café Flore, a Castro district institution where he is clearly a regular. “I’m getting 30 to 40 Facebook messages an hour.”

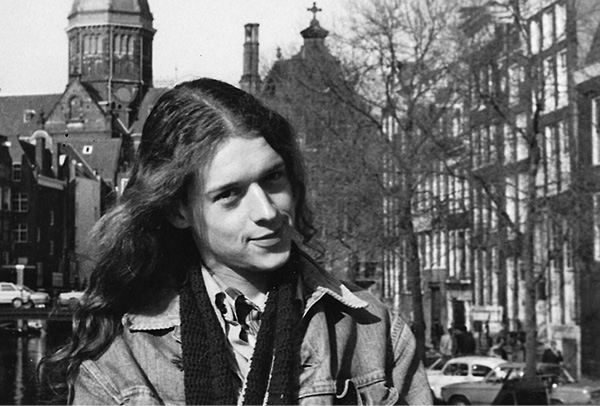

Cleve Jones as a young man in Amsterdam

Jones as a seasoned activist protesting at the Supreme Court Building

More recently, Jones paused to reflect before a section of the AIDS Memorial quilt

Focusing respectful attention on the gay community has been a huge victory in itself, Jones says. “It has to be the most inclusive representation of the LGBT community ever on television. The discussion about racism in the community and about relationships between lesbians and gay men was bold and complex.”

After lunch, Jones and I walk around the Castro neighborhood that has been his home for most of the past 40 years. He’s wearing a black T-shirt and jeans. The long dark curls captured in old photos — and sported convincingly by actor Austin McKenzie as young Cleve in the series — have given way to close-cropped gray.

Jones was an antiwar activist, out to himself but not his parents, when he first visited San Francisco at 17. He fell in love with the architecture, the radical politics and the young men in gay liberation T-shirts holding each other’s hands in public. He returned a year later after telling his parents he was gay and dropping out of Arizona State University.

He crashed with friends, slept in flophouses and hustled on Polk Street, one of thousands of young gay men flooding San Francisco. “We came to join the revolution,” Jones says, laughing at his youthful ardor. “We saw ourselves as foot soldiers” and marched against nuclear plants, for the ERA and in support of farmworkers. At some point, Jones entered the orbit of Harvey Milk, who owned Castro Camera and was a well-known activist.

We cross the street to Harvey Milk Plaza at Castro and Market, where a giant rainbow flag flies overhead. Created by Jones’ friend Gilbert Baker, it has become the global symbol of the gay community.

Baker, a self-described “drag queen [who] knew how to sew,” dreamed up the idea because the movement needed a life-affirming emblem to replace the grim pink triangle, used by the Nazis to brand homosexuals. Jones helped Baker raise money for the first flag and helped dye it. It flew in the gay pride parade of June 1978, the only one Milk rode in as an elected supervisor.

The plaza was the starting point for many protest marches led by Jones.

“We’d walk down Market Street, roar past City Hall and Polk Gulch, then up Nob Hill until marchers were so fucking tired they just wanted to go home, have some tea and smoke a joint,” Jones says.

This was part of Milk’s strategy for minimizing violence. “If you keep them moving, it makes it difficult for provocateurs,” Jones says. “They smash a window, you move everyone away. It limits their power and prevents clashes with cops.”

This strategy failed just once. On May 21, 1979, a jury acquitted Dan White of murder in the killings of Milk and Moscone, convicting him only of manslaughter. Jones led an outraged crowd to City Hall, where they erupted in fury, smashing windows and burning police cars in what became known as the “White Night riots.” Today, Jones sees that night as a turning point when gay people took a stand and fought back against police violence and impunity.

“I was raised a Quaker and I’m not a violent person but it was justifiable,” Jones says. “Afterwards, there was consensus to not apologize. And the next night, we had a huge party on Castro Street for Harvey’s birthday with no violence.”

“You focus on commonalities, not differences. We breathe the same air. We drink the same water. We need the same things.”

—Cleve Jones

For much of the 1980s, Jones divided his time between San Francisco and Sacramento, where he learned a different kind of activism, focused on legislative change. That work began with a chance encounter a few weeks after the killings.

“I was walking through City Hall and ran into Cleve,” recalls Art Agnos, who was a state assemblyman when he met Jones. “He said, ‘Agnos, if you ever need a f** to work for you, give me a call.’ Nine months later, I called him.”

At the time, there were no openly gay legislators or staffers, and Agnos warned him to be ready: “I said you’re going to be like Jackie Robinson. You’ll have to take a lot of shit.” That turned out to be true. In 1986, Jones was walking in Sacramento at night when two men called him “f*****” and stabbed him in the back. He was hospitalized and recovered.

In San Francisco, Jones led marches every Nov. 27 to honor the memories of Milk and Moscone. On that day in 1985, Jones was putting up leaflets about the march when he spotted a newspaper headline reporting that 1,000 San Franciscans had died of AIDS.

“My hair stood on end,” Jones remembers. “I knew almost every one of them had lived and died within six blocks of where I was standing. I remember saying I wish I had a bulldozer to knock these pretty houses down. If this was a meadow with 1,000 corpses rotting in the sun, people would see it and be compelled to respond.”

That night, Jones led marchers to the old federal building at United Nations Plaza and pulled out the red bullhorn left to him by Milk. “We’re here to honor Harvey and George,” he said. “But we’ve lost so much more. How many of you have lost someone? Write their names down.”

The marchers began inscribing the names of departed friends and lovers and taping them to the building’s stone facade. Later, Jones walked through the crowd. “You could hear people whispering, ‘I didn’t know he died.’ Or ‘I went to school with him,’” Jones recalls. “And you could feel this yearning — people needed to grieve together.”

“I looked at that patchwork of names and thought it looked like a quilt,” Jones goes on. “And this is where it gets weird: I closed my eyes and saw the national mall covered with fabric. It was as clear as a photograph in my head.”

In the crowd that night was Gert McMullin, a self-described party girl who had moved to San Francisco from Oakland in the mid-1970s. Days, she worked at the cosmetic counter at Macy’s. Nights, she worked in theatre and danced at Polk Street clubs with her gay male friends. “I was a wild child,” she recalls.

“On the street then there was a lot of random homophobic violence. But not at State. It was a very safe place for gay people to go.”

— Cleve Jones

In the early 1980s, her friends started getting sick and dying, and she began taking care of them. Eventually, more than 300 people she knew would die. When she heard later that Jones was planning to create a quilt, she called him. “I have a lot of friends who died and I know how to sew,” she said.

McMullin and other volunteers eventually set up shop in a Market Street storefront, and the AIDS Memorial Quilt began. Donations of fabric, sewing machines and money came in. And people all over began sewing and sending in panels. McMullin would come late each night after her other jobs, then work for hours with Jones, Jack Caster and other volunteers.

“I loved my friends, but watching them die one by one I felt I was dying,” she says. “Then I found the quilt. I could be with people who were going through loss. I needed that. I felt I wasn’t alone.”

McMullin made 130 of the quilt’s 49,000 panels, which represent some 94,000 people who have died of AIDS. It became her life’s work: When San Francisco rents got too high and the Names Project Foundation (the organization founded to act as custodian for the quilt) moved to Atlanta, she went as the quilt’s chief caretaker.

Today, she and Jones are a continent apart but remain close. She credits him for changing her life. “He made me an activist,” she says. “I don’t have a connection with anyone like I do with Cleve.”

Jones lived with HIV himself for a decade before becoming desperately ill in 1994.

He was fortunate. New medications had just become available, and he got them. Within two weeks, his immune system rebounded. Today, he takes three pills a day and is in good health. Now he can think about new threats.

“We survived Anita Bryant. We survived John Briggs. We survived HIV-AIDS. But what’s going to kill us is gentrification and displacement,” he says, pointing to a realty office. “Fewer and fewer gay people live in the neighborhood. The Cleve Jones of today, the 17-year-olds fleeing Trump’s America, can’t afford to live here.”

Since 2005, Jones has taken on a new fight as an organizer for the hotel union UNITE HERE. He’s proud of his work with the only private-sector union in the U.S. that is growing.

“You focus on commonalities, not differences,” he says of lessons learned from a lifetime of activism. “We breathe the same air. We drink the same water. We need the same things.”

As we continue along Castro Street, Jones points out building after building where friends lived and died. “I carry around a lot of ghosts and a lot of grief,” he says. “There are moments I need to get under the covers and cry. But I’m so fucking grateful I’m 62 and healthy. I have a job and a wonderful boyfriend I love.”