|

| |||

Inside the Photoreal World of On a rainy March afternoon, Robert Bechtle stands in the basement studio of his Potrero Hill home, impatiently considering a canvas. Just months ago, Bechtle's name flew on banners around Union Square, and thousands had visited the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art to see the first large-scale exhibition of his work. But for Bechtle, who taught painting at SFSU for more than 30 years, the buzz of celebration has been replaced by the frustration of getting back to work. On the canvas, brown lines sketch a row of suburban homes. "This is revisiting an earlier painting, which is something I'm interested in doing, because it will come out totally different," he says in a soft voice, touching his wiry white beard.

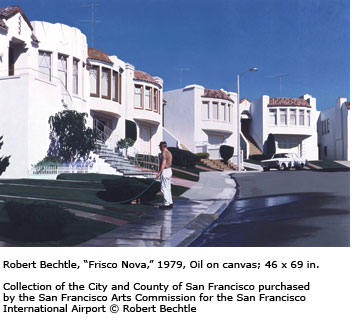

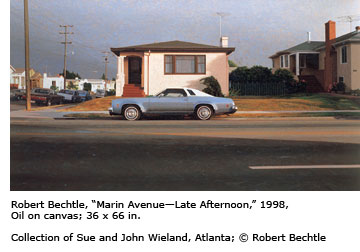

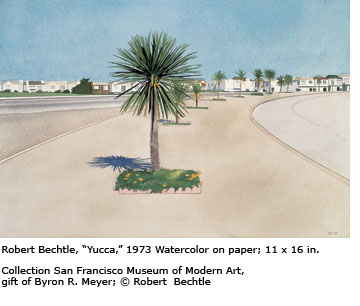

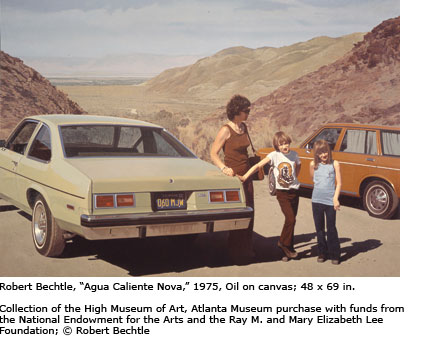

He doesn't just mean that the trees are now taller, and that a blue car is now parked on the street. The differences will be both more nuanced and more personal. After all, Bechtle does not draw and paint freehand, but projects his photographs onto canvases before meticulously filling in the details -- a process that, when he first adopted it four decades ago, struck him as "slightly naughty." He is the leading figure of the Photorealist school of painting, one of the most noted art movements of the late '60s and '70s. But while his works entrancingly re-create the look of an old family snapshot, the photograph is just a starting point for his art, opening up myriad choices about color and proportion, texture, and what Bechtle calls "a certain amount of fakery that is just technique." His subjects are as distinct as his methods -- placid streetscapes and '60s-era cars, backyard barbecues and other outtakes from middle-class family life, all awash in pale California sunlight and suffused with a subtly sad nostalgia. The paintings impart a strange feeling of loss, but they began as an attempt to avoid emotionality. "I didn't want emotion that was worn on the sleeve or had anything to do with the gesture of making art," says Bechtle, who grew up in the East Bay city of Alameda and attended Oakland's California College of Arts and Crafts. Reacting to such Bay Area figurative painters as Richard Diebenkorn and Elmer Bischoff, he adopted their subject -- San Francisco streets -- and tried to paint according to real life, instead of through memory. He was already turning that notion on its head when, one day in 1965, he began a painting of his wife and took a photo for reference. Shortly after, he decided to paint cars and, realizing that the proportions would have to be exact for the car to look realistic, used a projected photograph. "That was like a curtain lifting on all kinds of possibilities," he says. The curtain was lifting for other painters facing the same challenges. By 1968, Photorealism was a school. "It was a zeitgeist, sure," Bechtle says. "We were bouncing off the same framework of what art was about in California at the time, so we ended up making similar choices."

"Bob was an amazing teacher," agrees Noah Phyllis Levine, a former SFSU graduate student who served as Bechtle's studio assistant. "He was modest and unassuming, but it was so clear he knew what he was doing." At SFSU the shy Bechtle also met his second wife, art historian Whitney Chadwick. While he is professor emeritus, she continues as professor of art. They are married to this day. Bechtle's colleagues remember him as deepening the artistic dialogue on campus. "He's one of the few artists I know who could strike up a serious conversation about art at the drop of a hat," McLean remembers. "There was none of the social jousting that keeps the talk at cocktail-party level." And the landscape at SFSU fed Bechtle's work. He painted one shadowy floor of a parking structure because he thought the ambiance was "a little perverse." But mostly he painted the streets of the Sunset District, which he considered "an appendage to the campus." "I never wanted to be a tourist; I always wanted to photograph things I had a connection with," he says. "And being at San Francisco State, I felt I had a connection to that neighborhood." As acclaim for his paintings spread, his works became more charged, capturing stark midday light that cast ominous shadows across faces. "This sounds like black magic, but emotion comes out in the intensity of the work, and some painters have that and others don't," he says. "It's not conscious, and it's not a record of how the artist felt, but if the artist concentrates in an intense way, it allows the emotional flow to come."

If he imparted one thing to his students, Bechtle -- who retired in 1999 -- hopes it was "the old cliché of how to see." His fellow faculty members think he succeeded. "He would get people to slow down and look," Pratchenko says. "He's an artist who believes art isn't about fancy techniques, but a considered look at the world." Now he has more time to look, though he's busy with the retrospective's tour to Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C., and an upcoming show at Barbara Gladstone Gallery in New York City. But whatever further triumphs come, the SFMOMA show has sealed his reputation. "It was a triumph, a total knockout," McLean says of the exhibition. "I was impressed by the authority and strength of the show. It just confirmed for me that Bob is a painter of the first order. History will bear that out. He'll be right there with the famous artists we used to talk about." -- Rachel Howard is a freelance writer who lives in San Francisco. More: Where in the world are your former professors? | ||||

One of those fellow Photorealists was Richard McLean, an SFSU art professor whom Bechtle had known since art school; they would take their families on picnics together. In 1968, McLean recruited Bechtle to SFSU. It quickly became clear that Bechtle was as gifted a teacher as he was a painter.

One of those fellow Photorealists was Richard McLean, an SFSU art professor whom Bechtle had known since art school; they would take their families on picnics together. In 1968, McLean recruited Bechtle to SFSU. It quickly became clear that Bechtle was as gifted a teacher as he was a painter. His students saw the depth of feeling behind the technique. "I came to State in 1979 because I wanted to pursue a realist direction and Bob was on the forefront of that movement," says former graduate student Brian Yoshimi Isobe, who keeps in touch with Bechtle. "Years later I realized it wasn't the realism per se I was drawn to. He's a brilliant technician, but his paintings aren't about replicating a photograph, or technical virtuosity. The things between the lines in his work, the effect of things like the underpainting, are so subtle it's almost subliminal."

His students saw the depth of feeling behind the technique. "I came to State in 1979 because I wanted to pursue a realist direction and Bob was on the forefront of that movement," says former graduate student Brian Yoshimi Isobe, who keeps in touch with Bechtle. "Years later I realized it wasn't the realism per se I was drawn to. He's a brilliant technician, but his paintings aren't about replicating a photograph, or technical virtuosity. The things between the lines in his work, the effect of things like the underpainting, are so subtle it's almost subliminal."