|  | |||

A Way With Words The members of SF State's Forensics Team, a.k.a. the Speech and Debate Team, are settling into their desks when Megan McCallister enters waving a paper covered with red marks. "I just got my ADS back from Nicole," she tells her classmates. "I don't have a shred of dignity left." She is referring to her After Dinner Speech, a talk that aims to entertain as well as inform or persuade. The red edits are courtesy Nicole Sandoval (B.A., '06), a graduate student and volunteer coach. "Nicole is ruthless," explains Lisa Rau, a junior seated a few desks away. "She gives us a lot of comments on our speeches. I mean a lot. She puts so much passion into the job -- and she doesn't even get paid."

Forensics is the umbrella term for both Debate and Individual Events competitions. In Debate, students compete in pairs to argue the finer points of a single topic each year -- most recently, the First Amendment. "Debate invites students to drive their own education, to increase the philosophical things they are learning in college," Whalen says. "Students learn to ask, 'What is evidence and authority, and where do they come from?'" Each team choses an aspect of the topic to debate, then researches that subject extensively. The Individual Events competition includes informative, persuasive and impromptu speeches, and interpretation, in which students recite literature, usually excerpts from short stories, plays or poems. "We have a tapestry of really amazing students. There are the verbal go-getters but some are challenging their greatest fear," Whalen says. He enjoys watching students grow more secure in their own abilities. Defeats over Ivy League competitors certainly help, he says. "After a few semesters they say, 'Hey, I'm kind of good at this. I didn't get into this school, but I've beat them three times.'"

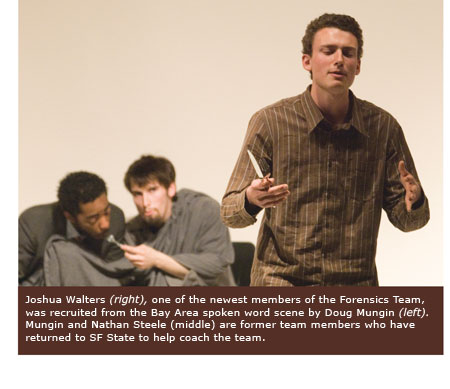

McCallister was among seven SF State students who qualified for national competitions earlier this year. Although 2007 did not bring any wins for SF State at these competitions, qualifying and competing was a significant accomplishment -- especially with the record number of novices who joined the team in the spring. Students work extremely hard to perfect their craft. Students can devote 20 to 50 hours per week to their debates and individual speeches depending on tournament schedules. But researching, writing and memorizing pages of text are only the beginning. Each category of forensics carries its own stringent set of rules. "You work within that framework," says Graduate Assistant Nathan Steele (B.A., '06). "But at the same time it's about pushing against the lines, trying to challenge that system." Last season, Rau took a risk with an informative speech, an event that tends to focus on new breakthroughs in research. While her competitors selected the latest scientific and medical discoveries as topics, she picked the ancient Mayan calendar. Her speech discussed the modern-day implications of ignoring lessons from the past. She performed it at the annual "Hell Froze Over" tournament at University of Texas-Austin -- a competition known to be as fierce as its name implies -- and placed second in the nation. Students learn from coaches who trained under Whalen. They know firsthand what it takes to succeed in forensics. In 2005, Steele and partner Robert Hawkins (B.A., '05) placed second in the nation in Duo Interpretation. Hawkins also placed first nationally in Dramatic Interpretation that same year. This kind of talk is not cheap. Even a weekend forensics tournament in the East Bay can involve substantial hotel fees. "It's an enormous struggle," Whalen says. "We have a small pool of money and lose competitive opportunities for students." Still, the team has won many debates and individual events, including the Regional Championship Tournament for the past seven years. Two students have been named All-Americans by the National Individual Events Tournament Committee, and eight have been named All-Americans by the Cross Examination Debate Association. In 2001, the University won the National Championship Sweepstakes Award. SF State's team has also defeated a number of formidable opponents including Stanford in 2003, Dartmouth in 2002 and Harvard in 2001, but Whalen isn't one to rattle off any of these statistics. Ask him what he's proud of and he lists names. Among them: Patrick Ip (B.A., '99), a hearing-impaired student who found a creative way to incorporate audio equipment into his competitions and wound up with a trophy, and Tony Bernacchi, a senior who learned Lakota for a rousing speech about the U.S. government's attempts to restrict Native Americans from speaking their own languages. Whalen's team members, who represent a variety of majors, find that forensics serves them well in other classes. Many say it has improved their ability to organize their thoughts, to construct arguments and to write. Debate has provided excellent preparation for aspiring lawyers, Whalen says, adding that other alumni of the forensics team include teachers, nurses and at least seven forensics coaches at Northern California colleges.

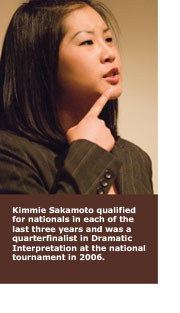

In May Sakamoto received the award for Outstanding Performer in Literature Interpretation presented by the Northern California Forensics Association. The organization named Rau Outstanding Performer in Platform Speaking. Whalen received the Distinguished Service Award. Success is always viewed as a bonus by the team's coaches. The overarching goal in forensics is improving students' communication skills, Steele says. "It's all about students being willing to engage with the world in a way that will hopefully make them more productive, better able to connect with each other, understand each other -- and ultimately, build community." Need a little polish at the podium? Check out Shawn Whalen's public speaking tips. -- Adrianne Bee | ||||

Passion is the name of the game in forensics -- for coaches and students alike. At the start of each semester, Shawn Whalen, the team's longtime director, warns students that speech and debate can be addicting. But first he clears up a common misconception. The Forensics Team does not perform crime scene investigations. "It's funny," Whalen says. "There is always at least one student who leaves right away on the first day."

Passion is the name of the game in forensics -- for coaches and students alike. At the start of each semester, Shawn Whalen, the team's longtime director, warns students that speech and debate can be addicting. But first he clears up a common misconception. The Forensics Team does not perform crime scene investigations. "It's funny," Whalen says. "There is always at least one student who leaves right away on the first day." McCallister, for one, considers herself stronger and braver than she was pre-forensics. The spunky senior with a flair for the dramatic admits she was once the quiet student who never said a word in class. "After being on the team, I have come to realize that even though people may not agree with what I have to say or my ideas, I have the right and almost the obligation to speak up."

McCallister, for one, considers herself stronger and braver than she was pre-forensics. The spunky senior with a flair for the dramatic admits she was once the quiet student who never said a word in class. "After being on the team, I have come to realize that even though people may not agree with what I have to say or my ideas, I have the right and almost the obligation to speak up." Kimmie Sakamoto, a graduating senior, believes the experience will serve her well in a future career in broadcast news. "Forensics has made me realize that whenever we are speaking, any changes in rate, tone and inflection can heavily impact how we come to understand each other," she says.

Kimmie Sakamoto, a graduating senior, believes the experience will serve her well in a future career in broadcast news. "Forensics has made me realize that whenever we are speaking, any changes in rate, tone and inflection can heavily impact how we come to understand each other," she says.