by Jesse Hamlin

With their wine winning accolades and her artwork the subject of a new book, these Gators have reason to raise a glass.

Wine the old-world way: Rob and Layla Fanucci's cellar at Charter Oak Winery is just as Rob's late grandfather, Guido Fanucci, left it. Today, the Fanuccis make wine as Guido did, and oenophiles confirm it's quite good. Earlier this year, Charter Oak's 2009 Monte Rosso Zinfandel received a 93-point rating at the Zinfandel Advocates & Producers Festival. Photo by Gabriela Hasbun.

Rob Fanucci still recalls the pleasure of sticking his fingers in a vat of fermenting grapes when he was 3, the rich smell and taste of the crushed purple fruit. He stood for what seemed like an hour in the cellar of his grandparents' house on Filbert Street in San Francisco, licking the luscious juice from his fingers.

"I couldn't stop. It was so sweet and good," says Rob (B.A., '78), who owns Charter Oak Winery in St. Helena. The small Napa Valley winery makes prime Zinfandel and Petite Sirah using hands-on, old-world methods and century-old tools passed on to Fanucci from his maternal grandfather Guido Ragghianti. The grapes in that vat hadn't yet fermented, but little Roberto became intoxicated -- by the winemaking process.

"I got mesmerized," says Rob, who as a kid helped his nonno (his grandfather, an immigrant from Lucca, Italy) pick and crush grapes. Rob is sitting in the spotless kitchen of the little yellow Victorian on Charter Oak Avenue in St. Helena where Guido lived and made wine until his death at 98 in 1986. Rob and his wife Layla (B.A., '81) -- a painter whose images are etched and painted on the double magnums of their Monte Rosso Old Vine Hillside Zinfandel -- make their wine and art here. It's the hub of a warm family enterprise.

In the back of the house is Layla's studio, a local historic landmark built in 1900. There she paints bold, multilayered cityscapes that hum with urban energy and motion. Rob, a lawyer whose office is down the street, punches down the grapes in half-ton bins out back, using big redwood bats that Guido made decades ago. The backyard vineyard provides the fruit for the Roberto Fanucci Estate Napa Valley Zinfandel, a hit at this year's international Zinfandel Advocates & Producers Festival in San Francisco, as was the winery's 2009 Monte Rosso vintage, made with grapes from the famed Sonoma vineyard planted in the 1880s.

Working with his son David, Rob hand-presses the grapes -- fermented with natural yeast from the property -- in his grandfather's 100-year-old basket press. The juice is pumped into French oak barrels in the little cellar beneath the house, where the wine ages 18 to 20 months before Rob begins the delicate and intuitive process of blending the flavors to find the right balance for each vintage. The cellar is exactly as Guido left it. There are dusty bottles of wine stacked against the walls, oval-framed family portraits, old tobacco tins and cigar boxes filled with screws and nails.

"We still do it the old-world way. You basically sleep with your wine," says Rob, a genial man in a black-and-white checked blazer, orange tie and jeans. "I'm around it all the time, always tasting it, smelling it, blending it. You can only make wine like this under these circumstances. This is a unique winemaking facility. It makes a unique product that can't be duplicated."

Rob studied political science at SF State and was captain of the debate team, an invaluable experience that he says gave him a great foundation for practicing law. He praises SF State's "progressive environment," and the speech and debate training he got from Professor Nancy McDermid, the retired dean of humanities. "It really prepares you for life after college -- how to make an argument, how to think on your feet."

Wine and art: When Rob and Layla took Guido and his wife Matilda out to dinner, Guido brought his own wine in a mason jar, "hidden in his jacket," Rob recalls with a laugh. "No corkage fee."

Layla taught music for 25 years before a trip to an art supply store changed her trajectory. Her cityscapes grace the pages of a book just out from the Walter Wickiser Gallery. Photo by Chick Harrity.

But he owes his wine skills to Guido. Rob shows a visitor his grandpa's old basket press, whose wood barrel is stained a deep plum color. It's out back past the chicken coop and a small cottage that is being renovated into a tasting room. It takes four to five hours to hand-press a ton of grapes; using an automated press, a commercial winery does it in about three minutes, says Rob, who produces only 600 to 800 cases of wine a year.

"It's hard work. But we get a gentler extraction," he says. "You're not squishing all the seeds, which are bitter, or taking all the tannins out of the grape skins, which could also make it a little astringent. It's a softer, silkier, more fruitful wine." Maybe Guido is watching over him, he says, proud to see him following the tradition, sprinkling a little magic dust to make the wine extra special.

Photo by Gabriela Hasbun.

In 1986, Rob, then working for Dean Witter, opted to stay in California rather than move back to New York with his division. At the time, he and Layla had two young daughters, Michelle, who would become an Emmy-winning TV producer, and Nicole, now a therapist ("Every family business needs a licensed therapist," Layla says with a laugh). They moved in with Guido, later buying their own home nearby. Before he died, the patriarch taught his grandson how to make wine as his family had done it for generations. Rob, who'd grown up drinking vino, was hooked.

"You just feel so alive when you're in the vineyards picking grapes, then crushing 'em and watching them ferment. I was badly bitten by the bug, and I knew I wanted to be in the wine business." He devotes 60 percent of his time to practicing law, the other 40 percent to making Charter Oak wines, which are sold in restaurants around the country, online and at the winery."We both work seven days a week," says Layla, a lively woman who put herself through SF State teaching voice and guitar while studying sociology. When she's not painting or playing the piano, she works in the wine business with her husband and son, an award-winning winemaker. They're respected vintners in the collegial but competitive Napa winemaking community.

"People really help each other out, but it is competitive," Rob says. "Everybody wants to get that top score, to make the best wine and get that cult status. Not everybody [reaches] that pinnacle."

Joel Peterson, who founded Sonoma's highly successful Ravenswood Winery, which produces about 800,000 cases of a year, is known as the "godfather of Zinfandel." He praises Charter Oak's wines. The process that Fanucci uses, he says, "harkens back to the core winemaking tradition that developed through trial and error over time and most often produced the most interesting, soulful wines." He finds those qualities in Fanucci's Zinfandels. "They clearly come from the heart, which is exactly what you want wine to do."

Layla's paintings are a labor of love, too. She quit teaching music in 2000 to pursue her other passion. Initially inspired by Matisse and Picasso, she developed a fluid, dynamic style of her own, creating dense, abstracted cityscapes with four to five layers of color and black-lined imagery. Bits of Manhattan skyline, for example, appear in the brimming surface of "Barcelona."

Layla's paintings are a labor of love, too. She quit teaching music in 2000 to pursue her other passion. Initially inspired by Matisse and Picasso, she developed a fluid, dynamic style of her own, creating dense, abstracted cityscapes with four to five layers of color and black-lined imagery. Bits of Manhattan skyline, for example, appear in the brimming surface of "Barcelona."

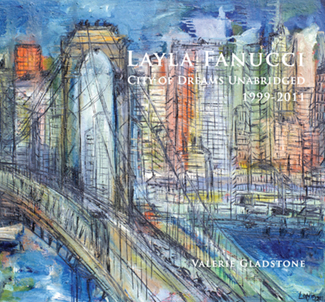

"All the layers bleed through, and it creates that luscious canvas. It gives you depth and texture," says Layla, who has exhibited at Morocco's Le Musée de Marrakech and New York's Walter Wickiser Gallery, which recently published a book of her work, "City of Dreams Unabridged, 1999-2011."

All the layers bleed through, and it creates that luscious canvas. It gives you depth and texture," says Layla, who has exhibited at Morocco's Le Musée de Marrakech and New York's Walter Wickiser Gallery, which recently published a book of her work, "City of Dreams Unabridged, 1999-2011."

The paintings, based on photographs and her experience of Florence, Paris and other places, portray "my version of a city," she says, gazing at a huge canvas titled "City of the World, Opus 5."

"When I go to a city, this is what I feel. I feel a little bit claustrophobic, but I love the excitement and energy," adds the artist, a native San Franciscan who grew up on the Peninsula and thrived on the urban energy at SF State.

"I loved the diversity there, people from different cultures and backgrounds. It gave me a different perspective on life and the world. That was my foundation."

For the Fanuccis, the arduous process of creating art and wine is intertwined, a joyous family endeavor that produces what Rob calls food for the soul. Making wine, he says, "is like painting. You make it with your own hands. There's a special enjoyment when you drink it." Like Layla's art, "it's a celebration of life."

See the story A School for Sommeliers