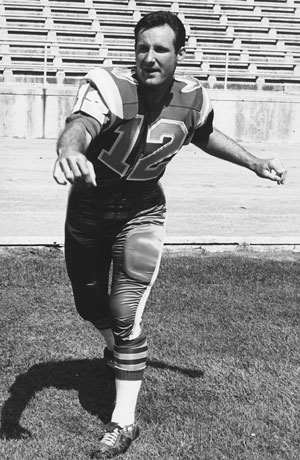

Twice all-conference quarterback Donald McPhail was inducted into SF State's Athletics Hall of Fame in 2011.

In 1963, San Francisco State wasn't a place for socializing or frat-house buddy-building -- at least not for anyone I knew. My three roommates on 16th and Castro -- Russ Hubbard, John Escobar and Bob Suter -- and I were older students struggling to get to classes on Muni, working nights and playing football. We won championships against Cal Davis, Nevada-Reno and other schools thanks to Joe Verducci and Vic Rowen, who had created a powerhouse small-college program.

Unlike most coaches, they welcomed players who were married, had jobs or hadn't made it at a big-time football school. They were straight with us; not exactly friends, more like parents who were patient with independent kids. Years later, I learned that Coach Rowen and a student-coach, Allen Abraham, had kept an eye on me long after I graduated.

The football program drew me to State. Before that, I was playing at the Naval Academy. I had been number two on Navy's depth chart, working to overtake a talented young quarterback named Roger Staubach. It was clear that I wasn't going to beat him out. This helped with my decision to leave Annapolis and take another path.

While I was finding a degree of success on SF State's team, Navy was ranked number two in the country, and Staubach was the nation's best player. But instead of marching to class with like-minded midshipmen, listening to youthful justifications for a new war, I was strolling the SF State campus and hearing perse points of view. I learned from professors Urban Whitaker and Marshall Windmiller that there has never been a just war, and that questioning authority is wise. Through Robert Wiseman, the greatest teacher I ever had, I discovered provocative writers: Aeschylus, Camus, Goethe, Rilke, Hölderlin and that Irish rascal W.B. Yeats.

Then, on November 22, just before 11 a.m. classes, the football, literature and talk of war were interrupted by gunfire in Dallas. President Kennedy had been shot. For hours we sat in the student union, listening to the radio broadcast over the P.A. system, refusing to believe. Our president was dead. The grief was spontaneous and profound. Students who had seemed disconnected and busy were drawn together, trying to absorb what was happening. Activists Marty Mellera and Bob Buffin, guys I seldom spoke to, became friends. Months later, as campus causes changed to anti-war and civil rights protests, I kept Marty and Bob in my thoughts as they rode buses to Mississippi and marched in Selma, and I understood why they went.

Events change cultures, and our culture was changed by JFK, Vietnam and the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy. It was changed by those who fought in Vietnam and by those who refused to do so. Early naïveté and idealism were blunted by these events and tempered into something else, partly because of shared experiences at SF State in the '60s. For some, they evolved into disbelief and cynicism. Somehow my own idealism grew into an outlook that, despite fractured politics and economic disparity, still includes regular glimmers of hope.

At SF State, I found an anchor before setting off in new directions. An independent, engaged campus culture helped and so did professors who were willing to guide my search for higher truths. I discovered the foundation of my social and political beliefs. My student night job at United Airlines turned into a 40-year career in the hospitality industry. My former coaches, Vic and Allen, became my personal friends. I became a writer. Valuable experiences for a young man who selected SF State just to play ball.

Photos courtesy of DONALD McPHAIL

Donald McPhail (B.A., '66) lives in Northern California with his wife, Gretchen. His first novel, ''The Millionaires Cruise: Sailing Toward Black Tuesday,'' was published in July. A former marketing executive for United Airlines, Hawaiian Airlines and Village Resorts of Hawaii, McPhail retired from the hospitality and tourism industry in 2007.