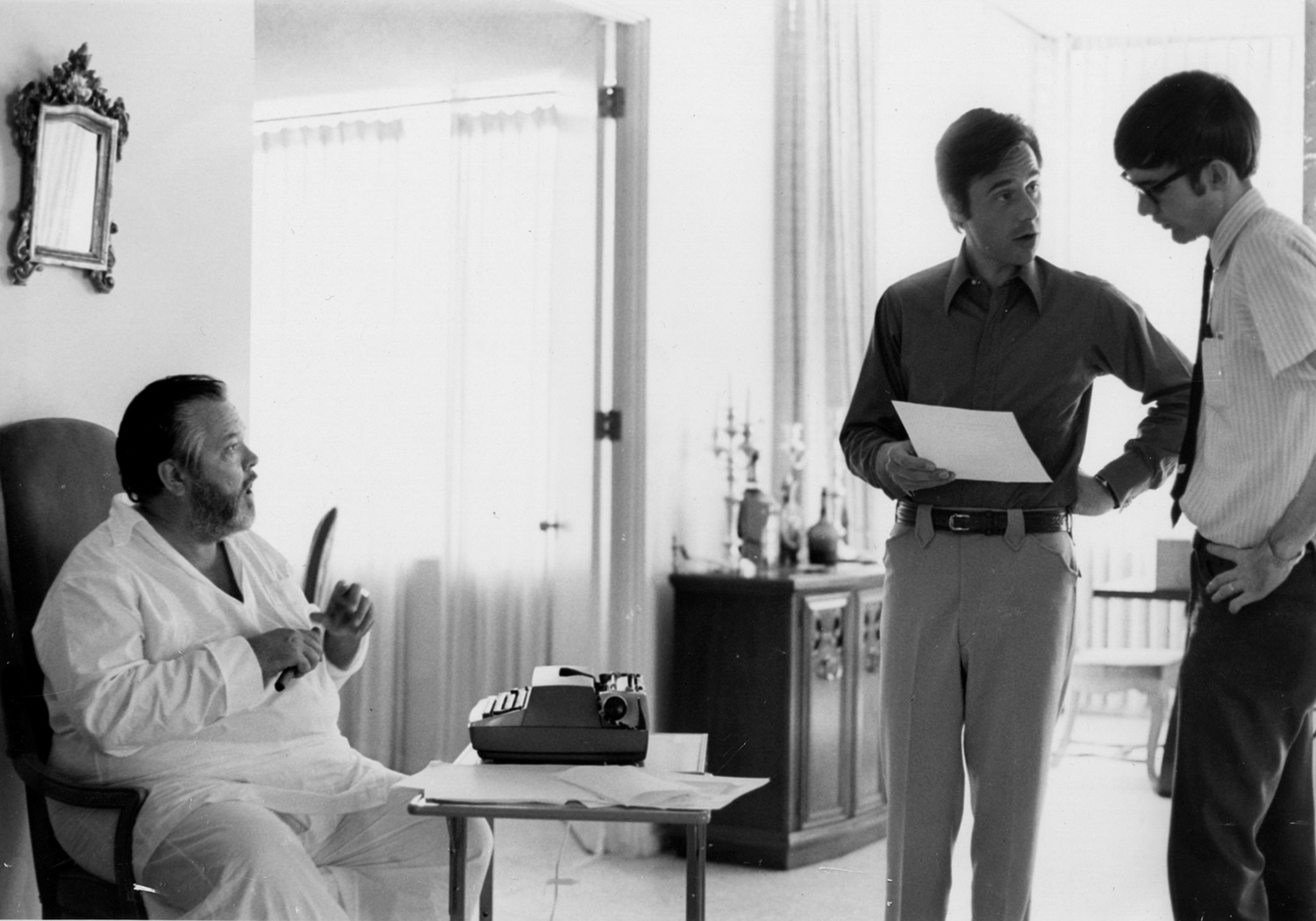

Welles (seated) and McBride (far right) on the set with Peter Bogdanovich

All's Well That Ends Welles

Although Orson Welles’ first movie for a Hollywood studio, Citizen Kane, is often called the best ever, as his career evolved the director came to prefer the often-rocky road of independent filmmaking. In fact, one of his last movies — a satire about Hollywood — was never completed and released…until now. The film, The Other Side of the Wind, has been rescued from limbo by Netflix. Not only will cinephiles get to see one of Welles’ final big screen efforts, they’ll get to see the first by School of Cinema Professor Joseph McBride. The author of the upcoming How Did Lubitsch Do It? (about director Ernst Lubitsch) and other books, McBride hasn’t just written extensively about the great auteurs of film history. He got to work with the greatest as an actor in The Other Side of the Wind.

When did you first meet Orson Welles, and how did you end up working with him on The Other Side of the Wind?

In 1970, while finishing my first of three books on Welles, I went to Hollywood for the first time, to interview John Ford. I called Peter Bogdanovich, whose work as an interviewer had inspired me and who had directed a film I admired, Targets. Peter said he was “on the other line with Orson”; he came back and said Welles wanted me to call him. The first words Welles said were, “We’re about to start shooting a film — would you like to be in it?” I was flabbergasted because I’d never acted before, but shortly I was before his cameras playing a comically earnest film critic and historian, Mister Pister, as I would be for the next six years.

Why did you end up working on the film so long, and why wasn’t it finished back in the ’70s?

Welles started the movie with his and his companion Oja Kodar’s own money but eventually needed more and made an ill-advised deal with a company run by the Iranian government. That led to a tangled financial and legal battle over the ownership that was not resolved until recently. Welles died in 1985, leaving 42 minutes of the film edited. An expert team has been finishing it in the complex style Welles intended.

You must have amazing memories of what for you was a Walter Mittyish adventure, being a non-actor appearing in a film with many major actors.

In 1974, when John Huston was cast as the lead, I went to Arizona to do more shooting. I opened a door, and he was pulling on his pants, so I apologized. When he emerged, I said I had been acting in the film for three years, waiting for him to show up. “You’ve been in this picture for three years?” he said with alarm, realizing what a surreal escapade he’d gotten himself into. I made myself putty in Welles’ hands but gradually learned a few things about acting, since he was the best director of actors in film history. When I arrived in 1974, Welles said, “My God! He’s matured!”

Over the next few decades, you built up quite a diverse resume — co-writing the cult musical Rock ’n’ Roll High School, co-producing documentaries about John Ford and Alfred Hitchcock, writing biographies and film criticism. What brought you to SF State?

I moved to the Bay Area in 2000 while finishing my biography Searching for John Ford. My son had moved to Palo Alto with his mother, so I wanted to be near him. I enjoy the opportunity to interact with students and find I learn as much from them as they do from me. It’s also an ideal job because it allows me to keep writing books, including some dream projects.

Sometimes Millennials and Generation Z get a bad rap for being technology-obsessed and incapable of appreciating anything old. Do they appreciate Welles or Ernst Lubitsch?

One of my pleasures of teaching is exposing students to classic films I love. Students respond well when they get the chance to see them. Showing Lubitsch films is a treat. Students find it amazing that films made long ago, such as his great romantic comedies Trouble in Paradise, Ninotchka and The Shop Around the Corner, are so fresh and witty, so sophisticated and advanced in their sexual attitudes, in fact much more so than most American films made today.