|

| |||

Getting Street Smart With Max Kirkeberg

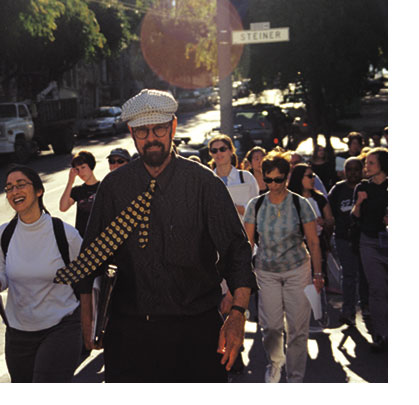

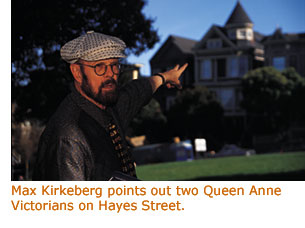

The group follows the instructor through Alamo Square Park, past a row of poplar trees, to view the celebrated Painted Lady Victorians on Steiner Street. Kirkeberg has only one firm rule for his students on today’s tour: “We must have a good time." Welcome to Friday afternoon in Georgaphy 454: "San Francisco on Foot." For the past 30 years, Kirkeberg has designed and led credit-earning tours that take students through the bustling Inner Mission to the rocky coastline of Land's End. "Max is a cultural geographer to the extreme," says Ellen McElhinny, a geography lecturer who co-teaches the class with Kirkeberg. "He knows a billion details about the city." If there were time, Kirkeberg, who triple-majored in geography, political science and history, could tell his students when each house on today's tour was built, what it's made from, and what used to be in its place. During more than three decades of research he has collected detailed notes on each building. But with only 2 1/2 hours for each class tour, Kirkeberg carefully selects each stop along the city's streets. At "postcard row," home of the Painted Ladies, students learn that in 1894 the Victorian houses originally sold for $4,000. Today asking prices hover around seven figures. Kirkeberg points out the house with the butterfly-shaped gate and says it’s the former residence of novelist Alice Walker. The Victorian on the corner, he says, is a favorite shooting location for film studios. The owner grew tired of fielding calls from Hollywood and set the house up with its own agent. The next stop is the Archbishop's Mansion at 1000 Fulton Street. Built for the archbishop of San Francisco in 1904, the French chateau mansion is now an opera-themed bed and breakfast. Kirkeberg explains that the archbishop's former bedroom has been converted into "The Don Giovanni Suite." "A little ironic, I think," Kirkeberg says with a chuckle. "Max is hilarious and his class is such a great way to get to know the city," says senior liberal studies major Meredith Rosenberg. She enrolled to explore San Francisco a bit further before moving back to her native Los Angeles. "I've learned so much about types and styles of architecture," Rosenberg adds, "and I've seen places I didn’t know existed." Her favorite discovery has been an enormous sundial just outside the SF State campus in the Ingleside District. According to Kirkeberg, in 1915 it was the largest of its kind anywhere in the world. Kirkeberg finds that churches are the best places to look for clues about surrounding neighborhoods. "The pastors know their [churches'] history," he says. Today he tells students that the Third Baptist Church, on the corner of McAllister and Pierce, dates to the Gold Rush. Although the current membership is hovering around 3,000, Pastor Amos Brown worries that the rising cost of housing is driving his mostly middle class congregation out of the city. More than 40,000 slides of the city rest in carefully labeled boxes inside Kirkeberg's office. Early in the spring semester he grabbed his camera hoping to capture a small home on a large lot in Merced Heights that was likely to be replaced. The bulldozers beat him there. "I'm kicking myself," he says. At 70, the geographer refuses to slow down. Three years ago he temporarily gave up guiding tours to undergo a series of knee surgeries. McElhinny took over the walks while Kirkeberg continued with his Monday and Wednesday class lectures. Although he officially retired last year, Kirkeberg returned as a lecturer in order to continue teaching his favorite class. Some structures, like the bland San Jose Avenue building spotted on a recent tour of the Mission District, get the Max Kirkeberg classification J.A., as in just awful. "Students are free to disagree, but they have to tell me why they like or dislike anything we happen upon," he says. On weekends before the start of each semester, Kirkeberg and McElhinny walk each tour route. As real estate prices change, buildings are remodeled, and residents move, new questions arise. To find answers, the geographers swing by police stations, chat with people watering gardens, and drop off notes requesting informational interviews. Thanks to their legwork, today students learn what inspired an enormous sculpture of wire and bells on Fulton Street. It is the work of Ron Hingler, who lives in the artists' collective next door. Influenced by Tibetan religion, the sculpture's bells are intended to send prayers every time they ring. Students stop to take periodic quizzes designed to see if they know their Queen Annes from their Classical Revivals. But, Kirkeberg says, "It's more important to learn to look and to ask than to know all the answers." Jacob Goldman, a special education major from Santa Cruz, is taking the class to get to know the city better. "I find myself looking around and really paying attention to things I don't think I would have noticed before," he says. Goldman and his classmates have the chance to demonstrate their observational skills later in the semester when they design and lead their own walking tours. The class is limited to 25 students, but once they hit the streets the group always grows. A house painter just off work is the first to join today's tour in progress. Later, Brian Labrie, a curious neighbor, follows the group for several blocks. "This is so cool," he whispers. "I get to learn about my own neighborhood." In 1965 Kirkeberg left his home in Iowa for a teaching position at San Francisco State. He's glad he settled in the city before housing prices began to soar, but you won’t catch him longing for the good old days. Yes, things are more expensive. There's graffiti and the problem of homelessness, and it's difficult to find parking. Kirkeberg shrugs off these things with a smile. "Life in San Francisco in the '60s was great and it’s great now. This city continually feeds me," he says. There's still a sense of awe whenever Kirkeberg stands near his home in Bernal Heights and watches the fog roll in over Twin Peaks.And every walk is a new walk. Just the other day Kirkeberg discovered a new set of steps in Potrero Hill at the end of 22nd and Kansas. "These steps aren't even in Adah Bakalinsky's 'Stairway Walks in San Francisco,'" he says excitedly. To keep up with the changes within his seven square mile city, Kirkeberg tries to take a different route whenever he drives to State, the bank, or the grocery store. And he'll gladly watch any movie filmed in San Francisco. It doesn't even have to be interesting or have much of a plot. "Max knows the city so well, almost any scenic tip--part of a building or a tree--will let him place a specific area," McElhinny says. Recently the two teachers headed to the Castro Theatre for a showing of "The Sniper" a black and white '50s-era serial killer film. "I'm watching this gruesome story unfold and Max keeps elbowing me and shouting out things like, 'Look, there’s Calhoun Street!'" McElhinny says. In Kirkeberg's investigations of the landscape of San Francisco, he’s even established Kirkeberg's Law: People don't shop uphill. Youwon't find commerce on the city's steeper streets. His tours don't go uphill, either. When Kirkeberg first began his tours as summer weekend classes at State in the '70s, he remembers a group of teachers panting behind him as they trudged up the Filbert Steps. "These people were mad at me for an entire weekend," he says. "I learned that I don't want to do a walking tour where people are struggling for breath." Each tour ends with a half-hour discussion while the tour is still fresh in students' minds. Today's walk concludes at 824 Grove Street, the home of Kirkeberg's friend, Dick Reutlinger. "You really become a group--you’re forced to get to know each other," says Gretchen Fischer, a senior in anthropology. "Max is just a great guy," she adds. "I overheard some of the older ladies in the class whispering to each other that they wished they'd had a professor as entertaining as Max back in their undergraduate days." Fischer enjoyed the class so much last year she's taking it for a second time. "When we start out most people don't know each other but it’s a shared experience," Kirkeberg says. "We wind up in each other's cars and everyone bonds much like a pledge class. The tours give us time to get to know one another." As his understudy, McElhinny sometimes feels overwhelmed by Kirkeberg's encyclopedic knowledge of the city. Should the tour guide ever decide to hang up his walking shoes, McElhinny knows they will be difficult to fill. From all appearances, the geographer has no plans of stopping. For Kirkeberg, the reward of his tours is watching students learn to look and wonder about their surroundings. It's a trait he hopes they'll carry with them wherever life takes them. More: Max Kirkeberg's favorite spots. | ||||

The tours are steeped in architectural lessons. Students learn to differentiate between such styles as Italianate, Queen Anne, Edwardian, and Stick.

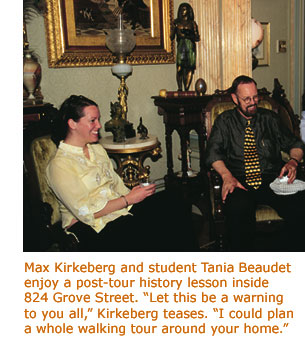

The tours are steeped in architectural lessons. Students learn to differentiate between such styles as Italianate, Queen Anne, Edwardian, and Stick. Sitting inside the Victorian's cozy antique-filled living room sipping punch and discussing architectural history with Reutlinger, it feels more like a family gathering than a class.

Sitting inside the Victorian's cozy antique-filled living room sipping punch and discussing architectural history with Reutlinger, it feels more like a family gathering than a class.