|

| |||

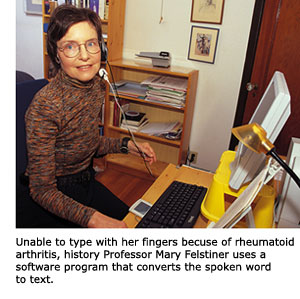

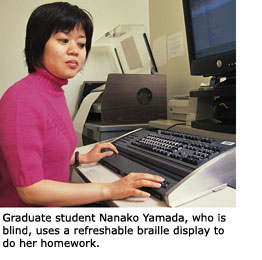

Breaking Barriers Mary Felstiner, a history professor at San Francisco State, has had rheumatoid arthritis since her early 30s. Today, at 62, the stiffness in the joints of her hands is so severe that Felstiner can barely sign a check or type an e-mail message longer than, "Sure, let's meet at 5." Still, Felstiner, a nationally recognized expert on women and genocide, is a prolific writer. She is at work on her second book, contributes frequently to scholarly journals, and generates a steady output of memos, letters of recommendation and reports. Felstiner accomplishes most of this without lifting a pen or touching a keyboard. For the past two years, she has used Dragon NaturallySpeaking, a speech-recognition program that converts the spoken word to text. Writing this way is frustratingly slow, she says. Each correction involves as many as 10 verbal commands that Felstiner utters into a headset microphone attached to her computer. But it's vastly preferable to anything else she's tried. "For me, this is wonderful," Felstiner said. "It's enabled me to be independent, and that's the name of the game." Felstiner's experience is an example of how adaptive technologies are helping students, staff and faculty with disabilities at San Francisco State gain full access to campus life in startling ways. Some devices, like Felstiner's speech-recognition program, rely on highly sophisticated technologies; others are as simple as a height-adjustable keyboard drawer for people who need to type standing up. Big-Ticket Items Adaptive technologies can be expensive. The University's refreshable braille display, a device that allows blind people to read text on a computer screen, carries a price tag of about $10,000; screen-reading software such as JAWS, which converts text to speech, costs up to $900 to license. With an annual budget of about $1 million, the Center can't afford to buy everything. "But if somebody comes in and needs something and we determine it's a reasonable accommodation, we'll work within the University to find the resources to pay for it," said Gene Chelberg, the Center's director. The University's most extensive collection of adaptive computer technologies is located in the Maurice K. Schiffman Room in the lower level of the J. Paul Leonard Library. Here, behind a locked door with a card-swipe entry, are computer programs such as ZoomText, which magnifies the text on a computer screen so that it can be read by people with vision problems, or OPENBook, which converts scanned images to speech for people who are blind or have cognitive problems reading the written word.

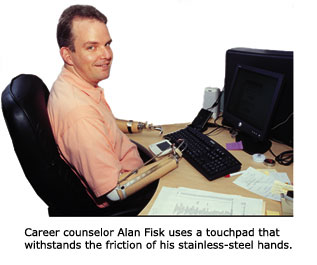

Yamada runs a slender index finger from left to right along the braille pegs as she proofreads her paper. Her finger stops on a cell where she has found a grammatical error. She reads it aloud. "Therefore, parents should know what their child learn -- it should be 'learns.'" She quickly corrects the error. Yamada, a special education major, said the braille display improves the quality of her schoolwork. More importantly, it helps her be self-sufficient. "I used to ask my friends to edit my papers for me. They're nice and they didn't mind, but I prefer to do things for myself," she said. Born without lower arms, Alan Fisk, a career counselor at San Francisco State, wears prosthetic arms with hands made of stainless-steel hooks. Fisk types "the two-fingered way." It's slow but it gets the job done. His bigger concern is moving the cursor. When mouse technology came along, Fisk found he could grasp the device using both hands but doing so fatigued his arms. Trackball mouses were better but not ideal. Fisk can manipulate the trackball with the eraser ends of two pencils that he grasps in his hands. But in order to type, he has to release the pencils then pick them up again to use the trackball. Fisk knew there had to be a better way. SFSU's Go-to Guy For Fisk, Grott figured that the best solution would be a touchpad. He experimented with different brands and models before finding the Cirque Corporation's GlidePoint touchpad, which bears up under the friction of Fisk's metal hooks. Grott made Fisk a tilted, plastic base so that the touchpad sits at the proper angle for his hands. "People's needs are very individual," Grott explained. "Even when off-the-shelf products exist you have to customize them to suit the particular person."

His Left Foot There was one hitch. Since Longmore could use his right hand only with great difficulty, he would have no way to scroll up and down or open a new document. Longmore got on the phone. "Hey, Ray, got any ideas?" Grott knew that Longmore had considerable mobility in his legs and feet. He located a foot pedal that would connect to Longmore's laptop through a keyboard port. The pedal has three switches; Grott programmed one to scroll up, another to scroll down, and a third to toggle between documents. In the HSS building, where Longmore teaches "American Colonial History," the pedal sits on the floor near his left foot. Longmore can reach it easily without glancing down, much in the way that a driver reaches for a clutch pedal. "It's working out great. It's just making lecturing a lot easier because I can sit down and see my notes and not have to worry about turning pages," Longmore said. No Easy Solutions Palmer uses a guide dog to get around campus. To aid her hearing, she wears a cochlear implant, an artificial hearing device that is surgically inserted into the inner ear. But even with the implant, Palmer would have difficulty hearing her professors were it not for an assistive listening device loaned to her by the Disability Programs and Resource Center. For the most part, the device, which is called PhonicEar, works great. In Palmer's class on substance abuse, for example, her professor, Janet Buchholz, speaks into a lapel microphone that is clipped to her blouse or jacket. A slim cord connects the microphone to a small FM radio transmitter that Buchholz carries in the pocket of her slacks. The transmitter sends Buchholz's voice to a tiny receiver in Palmer's jeans pocket. From there, it goes to a speech processor clipped to Palmer's waistband. The processor converts Buchholz's voice to electrical impulses and dispatches them up to Palmer's cochlear implant. The assistive listening device makes it possible for Palmer to hear Buchholz just fine. Hearing what other students say is not as easy. While a second microphone is passed around during class discussion, many students forget to use it or can't be bothered. That's frustrating and unfair for Palmer, who is shut out of the conversation because she has no idea what her classmates are saying. "It's like, OK, pass the mike! Pass the mike!" Palmer said. "It makes me feel kind of isolated." But Palmer isn't the only one who misses out when her classmates don't use the microphone, said Anthony Moy, a staff member at the Disability Programs and Resource Center. Since Palmer can't join in the discussion, her classmates don't get the benefit of whatever she might have to say on the subject at hand, he said. "This is an issue of access for all students, not just disabled students," Moy said. "Let's say the student who is being excluded happened to be Albert Einstein. Who is not benefiting now?" Finding the right adaptive technology can be a never-ending process. The minute one problem is solved, another can take its place. That's what happened to Felstiner, who damaged her vocal chords by overuse of the speech-recognition program. Today, her voice is so weak that she cannot talk to someone in another room in her small Palo Alto home. When Felstiner first started losing her voice, she panicked. She makes her living talking in front of groups of people. What if she couldn't do that anymore? Felstiner found a solution in a classroom voice amplifier, which, like the PhonicEar, operates on FM radio signals. During class, Felstiner wears a lapel microphone clipped to her blouse, and a small, black transmitter hangs on a strap around her waist. Her amplified voice comes out of two bookshelf speakers connected to a radio receiver/amplifier. Jumping Emotional Hurdles Instead, Wright said, she bobbed and weaved when she walked down the sidewalk. Getting to a meeting in another building on campus required so much physical exertion that she arrived soaked in sweat. "Finally, one of my colleagues said, 'What looks more disabled, you sopping wet and disheveled or using a wheelchair?'" Wright recalled. Today, Wright zips around in a motorized wheelchair, which is owned by the University and loaned to her for campus use. Wright said she still battles an image problem but she's thrilled with her chair. It's a sporty-looking, candy-apple red with adjustable speeds and a cup holder for her coffee. "The technology is there," Wright said. "The biggest obstacle is accepting the help. Ninety-nine percent of it is just getting past that psychological barrier." More: Gene Chelberg: Seeking the All-Access Pass -- Anne Burke | ||||