By Anne Burke

Academy Award-nominated filmmaker Arthur Dong (B.A., summa cum laude, film '82) is at a good place in life. His latest documentary, "Hollywood Chinese," is a hit on the festival circuit and recently won a Golden Horse Award, China's top cinematic honor. He's excited about an upcoming gig as curator of a Chinese-themed film series at American Cinematheque in Hollywood. Best of all is Reed, the chatty and chubby-cheeked 3-year-old who Dong adopted at six months, with his longtime partner, Young Gee (B.A., '81), an ESL professor at Glendale Community College.

But this morning, settled into a chair in the editing studio at his home in Los Angeles's Silverlake neighborhood, Dong, 53, is visibly upset. The morning paper carried shocking news of the fatal shooting of a middle school boy who had come out as gay. The night before, Dong watched a movie in which an Asian-American character spoke choppy and flawed English, for no apparent reason.The two provocations may seem unrelated. But in Dong's world view, both point to the intolerance and hatred that he has devoted his filmmaking career to fighting, most recently with "Hollywood Chinese," which explores yellowface and Asian stereotyping as part of a broad look at the Chinese in American feature films.

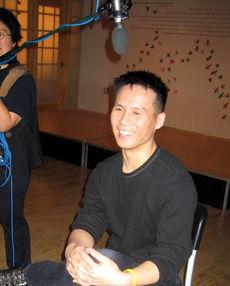

Arthur Dong, seen here with "Hollywood Chinese" cameraman Allan Barrett, says his film theory courses at SF State continue to

inform his work. — Photo by Young Gee

"I want people to realize that a lot of the problems we have in the world are based on stereotypes and perceptions of 'the other,'" Dong says. "So what I like to do in my films is have a point of view -- because to me a film requires a point of view -- but give audience members enough space so that they can flesh out what I give them at the beginning and make it their own. Don't tell me what I should be thinking, but guide me along and give me a road map," Dong says.

Dong was only 15 when he made "Public," a five-minute film about a child's reaction to violence and oppressive societal norms. The film, shot in Super 8 in Dong's bedroom at his family's home in San Francisco's Chinatown, won first prize in the California High School Film Festival. On the judge's panel that year was SF State faculty member Jim Goldner, who thought Dong's work was brilliant and encouraged him to enroll at SF State's film program.

Dong's first try at higher education faltered. Emotionally and intellectually, he was unprepared. He dropped out and embarked on a six-year odyssey filled with personal growth and discovery. He was a banker and a social worker. He studied accounting. In the Marin County woods, he made ceramic pots and learned to play a Chinese folk instrument.

During production of "Hollywood Chinese," Arthur Dong discovered two nitrate reels of "The Curse of Quon Gwon," a film produced in 1916. It is now acknowledged as the first known Chinese American film. — Photo courtesy of Arthur Dong

In the late 1970s, Dong toured China, taking along a video camera and a deep curiosity about his parents' homeland. On the long flight home to San Francisco, he passed time editing footage in his head. 'It reminded me of what I really loved doing, so that's when I went back to San Francisco State.'

Older and wiser, Dong was determined not only to graduate but to do so with top academic honors. In a film theory course taught by Ron Levaco, now a professor emeritus, Dong devoured the writings of the semioticians Jurij Lotman and Roland Barthes, whose ideas about signs, symbols, codes and syntax inform the filmmaker's work even today. John Hess's course on film and progressive social change "helped me articulate exactly what it was that excited me about film, and put it in a larger world context.

Even the English 101 course that induced sleep during his first stint at SF State was fresh and exciting. "How to form your essay, the hypothesis, topic sentences -- all that stuff. I thought it was so fascinating. So that's how you do it. I really felt that from that class, I had a strong foundation in how to write.

For his senior project, Dong chose a subject close to his heart. "Sewing Woman" chronicles the journey of the filmmaker's mother, Zem Ping Dong, from an arranged marriage in China to a San Francisco garment factory. Dong's sister, Lorraine (M.A., Humanities, '70), then a law student at the University of Washington and today a professor of Asian American studies at SF State, wrote the script. Almost as an afterthought, Dong submitted "Sewing Woman" for Oscar consideration in the short documentary category, and was thrilled when it received a nod.

SF State alumnus B.D. Wong is among 11 Chinese and Chinese American film artists who discuss racial typecasting in Arthur Dong's new documentary. Photo by Arthur Dong

In the nearly quarter century that followed, Dong has let his commitment to social justice guide his filmmaking choices. Among his best-known documentaries is "Licensed to Kill," a chilling look into the psyche of killers of gay men. (Goldner has shown the film in his documentary courses and calls is "a stunner.") From time to time, Dong delves into lighter fare. "Forbidden City" is a lively look back at an all-Chinese nightclub in San Francisco. In addition to the Oscar nomination, Dong has a George Foster Peabody Award, three Sundance Film Festival awards, and five Emmy nominations.

Though comfortably settled in Los Angeles, Dong retains strong ties to his alma mater and the Bay Area. He returned to campus in 2007 to accept alumnus of the year honors. Through "Hollywood Chinese," Dong has reconnected with old friends from State who've called to congratulate him on the film's success.

Above Dong's editing computer is a bookshelf with a yellow paperback. It's the same copy of Lotman's seminal "Semiotics of Cinema" that Dong purchased for Levaco's course a quarter century earlier. Dong said the author's name comes up fairly often in conversation with cinephiles who have a certain kind of academic background in film, but without State, he probably would have had no idea who Lotman was.

"It's interesting," Dong continues, "you talk to artists and filmmakers who didn't go through the educational system for their art, and they're, 'Ah, you don't need to go to school. You just do it.' But for me, without that strong foundation, I would feel haphazard. Getting that foundation gave me the ability to go off on a tangent and have fun with it."

Click here to read about "SF State on Film"

Back to Spring/Summer 2008 index