|

| |||

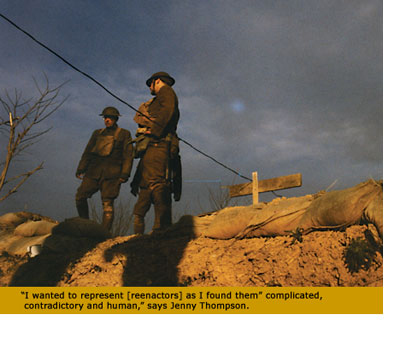

Ten years ago on a cold winter day in a remote wooded area in Pennsylvania, Jenny Thompson (B.A., '89) began some "in-depth" research for her Ph.D. in American studies. She put on a uniform, signed a waiver of liability and joined thousands of people preparing to go into the trenches to reenact the Battle of the Bulge. She hoped there was no truth to the tales of injuries by blanks or live ammo. "I was nervous," she recalls. "I didn't know what to expect." During the next seven years, she donned a uniform many times, ate K-rations and slept in the woods. She served as an ambulance driver, a correspondent and a Russian soldier. She got to know war reenactors from all walks of life, listened to heated debates on historical authenticity and was even captured and "executed" by German forces. The result of her lengthy investigation is "War Games: Inside the World of Twentieth-Century Reenactors" (Smithsonian Books, 2004), a book which reveals the motivations of reenactors, as well as the deep and far-reaching effects war has had on our entire nation. As Thompson writes in "War Games," "A war's reverberations are felt not only by those who experience it. They also echo through the lives of the children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren of soldiers and victims alike." During formal interviews and chats in the barracks, Thompson discovered that "like other hobbies, such as researching family genealogies, reenacting is a way to make active and personal use of history." Many reenactors told Thompson they were seeking to understand the war experiences of their veteran fathers who refused to speak about their time in combat. Others claimed that reenacting war is a way for them to honor fallen soldiers. Using words that sounded more appropriate for real veterans, some spoke of reenacting as their legacy. The more Thompson learned, the more contradictions and questions arose, pulling her deeper into her research. SFSU Professor Rodger Birt wasn't the least bit surprised to learn that his former student had been spending her time impersonating military personnel. "That's so Jenny," he says. "She doesn't want to circle around a subject and be in the periphery. She wants authenticity." Thompson displayed her appetite for learning in several of Birt's undergraduate courses as she worked toward her bachelor's degree in humanities. He knew she had the makings of a first-class scholar. "She wants to learn as much as possible," Birt says, recalling how Thompson engaged in independent research projects along with the required work. "She's intellectually honest, takes no short cuts." Thompson credits Birt with encouraging her to get her Ph.D. Growing up in Marin, Thompson enjoyed watching movies in the genre of "All Quiet on the Western Front" with her father, a poet and painter with an interest in military history. "I've always been interested in how war is represented and remembered in our culture, how it changes from one generation to another," Thompson says. After graduation, she pursued her master's degree at George Washington University. Her thesis focused on the effect the American government and media had on the public image of World War I. Only when she began course work toward her Ph.D. at the University of Maryland did she learn there was such a thing as twentieth-century war reenacting. After years of researching the ways war has been represented and remembered in our culture, Thompson was surprised and intrigued to discover that 6,000 people across the country are members of reenacting units that recreate World Wars I and II, as well as the Korean and Vietnam wars (commonly referred to as "doing the Nam"). Unlike the more familiar Civil War reenactors, here were people playing foreign soldiers, Nazis and Vietcong. Emotional wounds were still raw. Time had not yet created a safe When she decided to take a closer look by "enlisting" herself, some of Thompson's friends and grad school colleagues wondered what she was thinking. War reenactors were a bunch of kooks, they told her. And it just isn't right to make a game out of a subject as serious as war. Thompson wasn't interested in promoting reenacting. She was looking to understand its participants. Although she initially thought she would learn about reenactors by exploring the ways that they are disconnected from society, her investigation led her to believe that "the hobby is a product of normal life in America." The reenactors Thompson encountered were not on an island. They came from every socioeconomic background. There were construction workers, teachers, doctors and lawyers. Fathers brought their sons. Although it is a male-dominated hobby, there were women, too. There was even a golden retriever who played the part of a Russian anti-tank dog. She believes that the very existence of reenacting forces us to hold a mirror up to ourselves. "As a culture we are not only shaped but also fascinated by war -- or, more broadly -- violence. â¦we promote, package, and profit from war." In "War Games," Thompson asks readers to consider how much reenactors' motivations differ -- if at all -- from the motivations of those seeking entertainment in depictions of war in books, movies and on TV. Past and present alike continue to impact the unusual hobby. Along with the surge of patriotism following the events of Sept. 11, Thompson discovered that participation in reenacting likewise began to increase across the nation. As long as Americans go to war and as long as there are descendants of veterans, she believes reenacting stands to continue for generations to come. After seven years in the trenches, Thompson managed to unravel much of the mystery behind reenacting, but at least one question remains for her. During a World War II event, where Thompson dressed as a correspondent "attached" to the U.S. Fourth Armored unit, she was surprised to hear her name at mail call. She stepped up to receive a personal letter from a publisher who did not exist, thanking her for her hard work on the battlefield and encouraging her to stay warm. Thompson still has no idea who wrote the letter. For more information: www.jennythompson.org -- Adrianne Bee | ||||