Ray Tadio photo by Juan Montes

Makuakāne portrait photo © John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation

Professor of Dance Ray Tadio and alumnus Patrick Makuakāne are both winning praise for the unique ways they use traditional dance to express their cultural identities

By Jamie Oppenheim and Matt Itelson

The movements of dance are found anywhere humans are on the planet. We may move differently, but we all move to the music. It tells us the stories that our ancestors wanted to know, to move with, to feel in our bones and our hearts. To keep new generations moving, an alum and a professor from SF State are preserving the dances of their respective homelands.

Patrick Makuakāne: moving hula forward

Most cultural preservationists look to traditions, artifacts, history and language to keep a culture alive and intact. But that’s where alumnus Patrick Makuakāne (B.S., ’89), a kumu hula (master hula teacher), bucks tradition. His unique interpretation of the art form, which he calls hula mua (Hawaiian for “forward”), combines sacred elements like chanting, singing and traditional choreography with modern touches like techno music and themes drawn from contemporary culture. (His show “Mahu,” performed at several Bay Area venues last year, celebrates transgender artists.)

His groundbreaking work in hula at the San Francisco dance school he founded in 1985 earned him a 2023 MacArthur Fellowship in cultural preservation, a recognition that came with a generous stipend of $800,000. He’s the first native Hawaiian to receive the honor, and he was among 19 other fellows from more traditional disciplines such as science, poetry, art, law, music and math.

The 62-year-old has made it his mission to challenge what’s considered traditional. “When people think of tradition, they view it as fixed or immobile,” he says. “You can still preserve culture and innovate at the same time. They’re not mutually exclusive pursuits. In fact, if your culture does not innovate or evolve then it becomes immobile and a dead culture.”

A raconteur, Makuakāne tells both old and new stories through hula. Traditional hula dances focus on the land and the Hawaiian people, but his choreography touches on edgier topics like imperialism and occupation. His 1996 production “The Natives Are Restless” explored the tragic history of Hawaii’s transformation from a sovereign monarchy to being annexed by the United States, which had overthrown the island nation’s first and only queen.

“I did this piece called ‘Salva Mea,’ which was about the missionaries. I dressed as a priest with techno music in the background and I was running around the stage with an 8-foot cross baptizing people,” he says. “It was like an incoherent, messy and incautious mix of tradition and experimentation that really worked. … People were blown away.”

That production set him on a path of experimentation ever since.

Photo courtesy Patrick Makuakāne

A place to feel unshackled

Makuakāne credits San Francisco — a city known as a playground for experimentation and boundary pushing — with being the perfect place for his art. Makuakāne arrived in the city around the time of Act Up, a grassroots political group working to end the AIDS epidemic. The group was known for its theatrical acts of civil disobedience, actions he calls influential.

He began studying hula at 13 years old. At 23, he moved to San Francisco for love, following a boyfriend who was a waiter at an exclusive French restaurant. After arriving in the city, Makuakāne taught hula to earn money. It was also his tie to Hawaii. He quickly attracted students and founded his award-winning hula school Nā Lei Hulu I Ka Wēkiu (which means “many-feathered wreaths at the summit”). Over the past four decades, he’s taught thousands of students.

While he was building up his dance company, he studied Kinesiology at SF State. After graduating he continued teaching hula and working as a physical trainer. As his school grew, he devoted himself full-time to hula, a decision that’s paid off both literally (like when the MacArthur Foundation called) and figuratively.

“[A friend once said,] ‘It must be nice being in San Francisco without someone looking over your shoulder, critiquing your every move.’ I was like, ‘Yeah it is,’” he says. “So that sense of liberation in your arts, feeling unshackled and doing whatever you want, was a part of my process. I feel like I’m at a place really where I can do anything.”

Photo courtesy Miriam Smith

Ray Tadio: dances no longer forgotten

Throughout the 7,640 islands of the Philippines lie thousands of dances. Methods of movement passed down for generations tell the stories of an archipelago bustling with rich culture, diversity and spirituality. But many dances are not recognized in the canon of Filipino dance, despite being in existence for hundreds of years.

SF State Associate Professor of Dance Ray Tadio is poised to change that — reviving one dance he’s heard about since childhood and two others that were not exposed to him. In 2020 he put a plan in motion. It began with a sabbatical proposal and would expand to a one-hour documentary for public television, with support from SF State’s Department of Broadcast and Electronic Communication Arts. The documentary, “Forgotten Folk Dances,” will premiere on KQED in San Francisco and other PBS stations in October.

“It’s a little surreal for me, seeing myself on the big screen,” Tadio says. “This is very personal. There are moments when I’m really vulnerable, and they caught that on film. It shows a raw human emotion.”

Land of a thousand dances

Music and dance are omnipresent in everyday life in the Philippines, providing Tadio with some of his earliest memories. “I can’t even remember not dancing,” he says.

He learned folk dances in his hometown, San Narciso, located in the province of Zambales on the northern part of the Philippines. His elementary school taught folk dances alongside the area’s native language, Ilocano, as well as the national language of Tagalog and English. “I had an idea already of what I wanted to research when I was little,” Tadio says. “I would see and perform certain dances. I would also hear of certain dances from the past such as the Spanish-influenced ‘Rigodon di Honor di San Narciso.’”

Tadio never stopped dancing after immigrating to the Bay Area at age 11. He trained at the Alvin Ailey School in New York and performed with acclaimed troupes worldwide before joining the SF State faculty in 2008. He has traveled to the Philippines about twice a year to visit his mom and family and, through his research, discovered that his hometown’s “Rigodon di Honor di San Narciso” was among the dances not recognized or published by the Philippine Folk Dance Society.

Tadio’s uncle, John Fontillas, a dance historian also from San Narciso who appears in “Forgotten Folk Dances,” recommended two other dances to explore in addition to the “Rigodon di Honor di San Narciso.” “Baile en Honor a Maria” is a ceremonial rural dance influenced by Catholicism and “Talipe” is a mimetic dance of the indigenous people, the Aeta. The film captures the three dances performed by students at La Paz National High School in San Narciso.

Justin Dionisio (B.A., ’20) visited the Philippines as a child, but these travels provided him new perspectives on his ancestral homeland. At SF State, he immersed himself in the Filipino community, joining the Pilipinx American Collegiate Endeavor (PACE) student organization, serving as president of the Chi Rho Omicron fraternity and performing folk dance at the annual Pilipinx Cultural Night. But traveling to the islands as an adult felt much different.

“Not only was I going there for school, but I was able to be more in touch with my culture and my cultural identity,” Dionisio says. “Being a college student, too, doing what I love — which is videography, photography and editing — it felt like my two worlds were colliding.”

Photo courtesy Jeremiah Ysip

‘I went back in time and met my ancestors’

It’s been a long four years since Tadio traveled to two regions of the Philippines, trailed by a crew of faculty, students and a BECA alumnus coordinated by Associate Professor Miriam Smith. With funding from SF State Foundation board member Camilla Smith and her husband George (both are credited as executive producers), they tapped Jeremiah Ysip (B.A., ’05) to direct.

January 2020 was a crazy time. The Taal volcano eruption delayed their trip for almost a week, and COVID-19 may have hit some of them unknowingly before quarantines went into effect. You wouldn’t know it from the vibrant, emotional footage they shot, not to mention the history and culture they discovered and the connections they made.

“I felt like I was in a time machine,” says Ysip, a third-generation Filipino American. “I went back in time and met my ancestors. There was an instant connection. It just felt like I’ve known them my whole life.”

Miriam Smith has long chronicled folk dance as a research interest and has enjoyed dancing since her upbringing in Utah. Since 2004 she has taken students as far as Hungary, Poland, Italy, Mexico, Russia and China to produce videos about global folk dance.

“We are transforming students’ lives by giving them an opportunity to tell stories of heritage, history, humanity and hope — in places they have only seen on television,” says Smith, a producer for “Forgotten Folk Dances.” “This is not my heritage story, but it is my humanity story. People are connecting with their heritage and doing it through dance and music. I mean, what could be more human than that?”

Ysip, a broadcast journalist who has won 11 Northern California Emmy Awards, says the experience was life-changing for him at a tough time in his career.

“It made me fall in love with storytelling again because at that point in my life I just didn’t want to do any of this stuff anymore. I’d just hit a wall,” Ysip says. “Miriam helped revive my career in that sense.”

Now that the documentary is in the PBS family, Tadio has made extraordinary movement on his goal to bring recognition to the “Forgotten Folk Dances.” But he’s not done. A new SF State course this fall, public workshops and more are coming soon.

Features

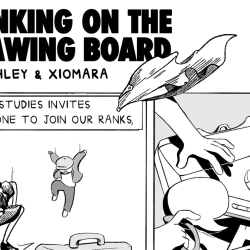

Novel Graphics

SF State students working toward a Creative Nonfiction Comics Making certificate tell the story of the innovative program through the very medium they’re learning to master: comics!

Facing the Music

Gator musicians step off the stage and in front of the cameras for a class project teaching Journalism students the basics of portrait photography.

In Conversation with Chris Larsen

Legendary journalist and Gator Ben Fong-Torres talks to cryptocurrency pioneer Chris Larsen (B.A., ’84) about the future of investing and why going to SF State was the “bargain of the century.”