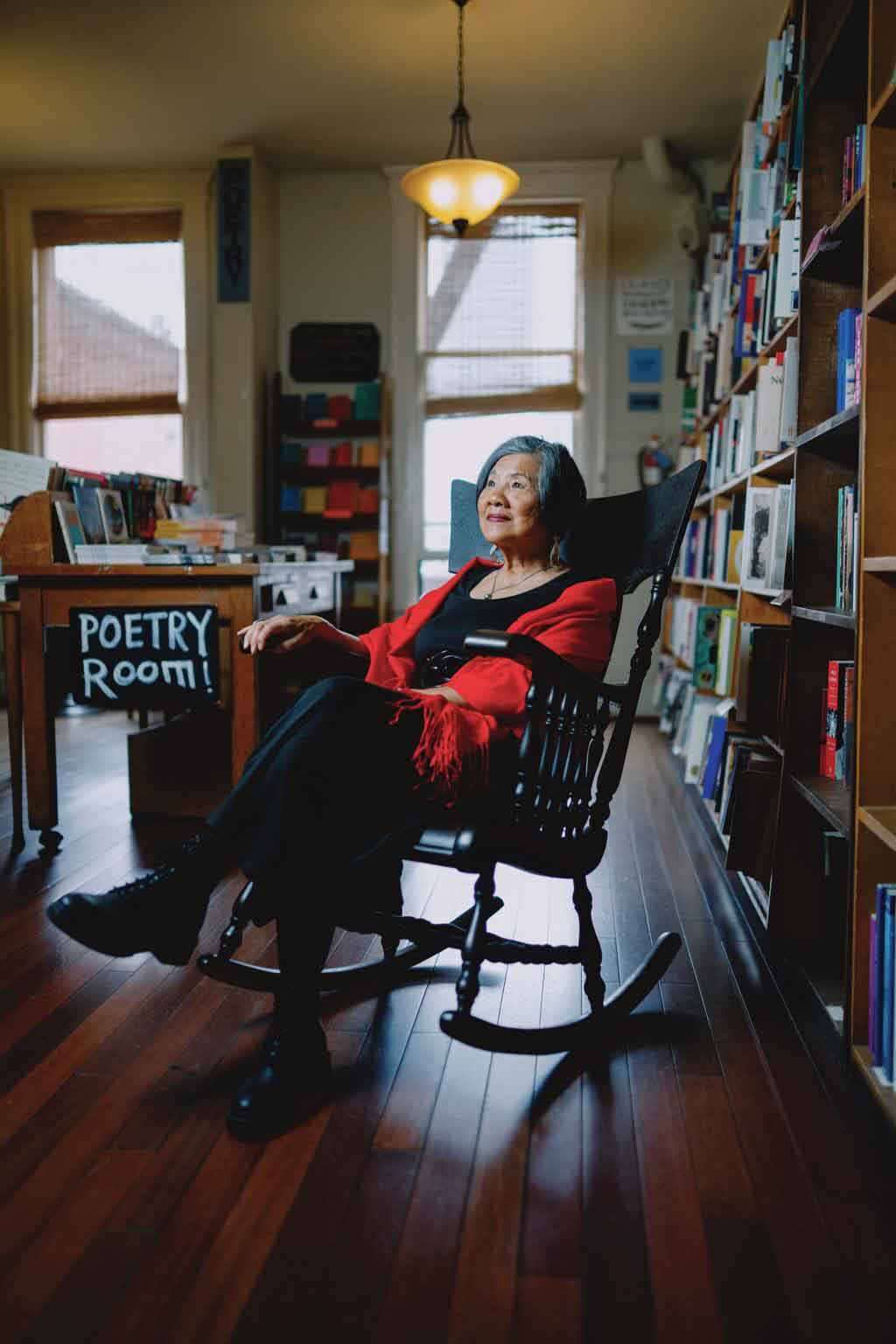

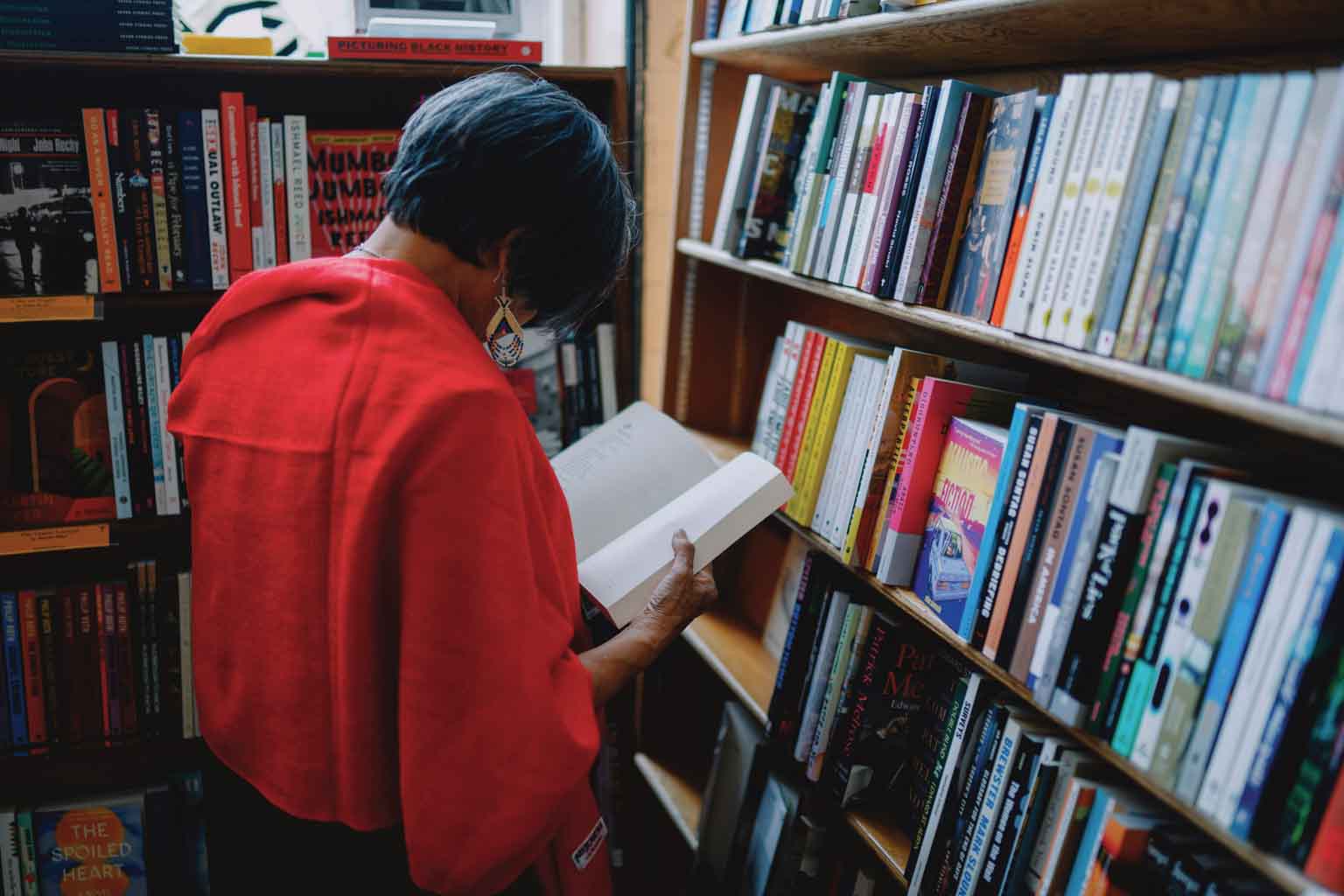

San Francisco Poet Laureate Genny Lim reflects on her journey from SFSU student to mentor, performer, teacher and icon

By Ben Fong-Torres

Genny Lim stood onstage at the Ritz-Carlton one evening last November to accept her induction into the SFSU Alumni Hall of Fame. After her remarks, she recited her inaugural poem, which she’d composed and performed earlier in 2024 when she was named San Francisco’s ninth poet laureate. She’s the first Chinese American thus honored.

Lim didn’t just say the title. She declared it: “I Am American.” She dove into a travelogue of neighborhoods and their residents, a catalog of their work, dreams and sacrifices, and as she did so, she achieved a percussion to her poetry. The guests in the ritzy ballroom exploded with cheers.

She concluded:

This is what it takes to pick yourself up

When beaten or disgraced

This is what it means to rise above

When silenced or erased

This is what it takes to Smash the window of despair

To fly through the looking-glass air

With wings spread wide

Proclaiming, “I am American!”

And the audience exploded again.

It was a far cry from the first time I met her, one day early in 1966, in the old Creative Arts building. She was in a talent show, “Kampus Kapers,” singing “As Long as I Need You.” I was doing a story for the campus daily, The Daily Gater.

Lim was the only Chinese American on stage. I was the only one who was an editor at the paper. We became good friends. Over the decades, I enjoyed watching her ventures in music, poetry, theatre, books, teaching and social activism.

Her zigzag career includes her education. She dropped out of SFSU during the student strike of 1968. She moved to New York and enrolled at Columbia University. She returned to SFSU and received her B.A. in 1977. She earned her M.A. in Creative Writing in 1988.

It’s the mid-’60s, and you were a theatre arts major and the only Asian American in the drama department. What was that like?

Pretty lonely. When I would look in the casting billboards for parts in department productions, all the parts seemed to be for white people, white characters. And in those days, there wasn’t any non-traditional casting at all. What I did end up doing was Theatre of the Absurd. I would play the chairs in Ionesco, as an absurdist character. It could be anybody, pink, blue, because it’s the storyline.

The one production that I really was fond of was Euripides’ “Bacchae,” because the director, Paul Rebillot, was gay, and he was very expansive. He had music, he had the bacchants and a diverse cast with an African American … and me. And he encouraged the chorus to be like Amazonian Bacchae women, so we really got into that spirit.

Rebillot was really inspiring, [but] the rest of the program was very conservative and traditional theatre, and it didn’t suit me. I did things outside of the campus. There was a theatre, Interplayers. I was in a production about an interracial couple. It was controversial, and then I sing this song, “Am I Too Different for His Love?” [Laughs.]

After I started doing things off campus, I got more interested in music and eventually creative writing, so I dabbled in the music department and singing.

Was there anybody in the Creative Writing section who was particularly helpful?

An important mentor was Kay Boyle, who took my writing seriously and gave me encouragement and important feedback on my short stories.

And there was Stan Rice (B.A., ’64; M.A., ’66). The vampire husband [laughs] of Anne Rice (B.A., ’64; M.A., ’72). He was very impactful. I took poetry and writing classes from him. He was very honest when I started to write. He was very bold and said, “This is B.S.,” but nicely, when I was trying to write and not coming from a real, honest place.

Then I took a beginning playwriting course from Bob Gordon. That’s where I began my first play, “Paper Angels.”

Theatre, music, poetry, plays — you were all over the place!

I was just dabbling and trying to find myself.

You were dabbling, but it was all under the umbrella of creative arts. Yet you came from a traditional Chinese family, living just two blocks north of Chinatown. Was there any pressure from your parents that this is not what you should be studying?

They didn’t really know the extent of my dabbling. They thought as long as I was pursuing my studies and I said I was going into teaching, that was all respectable to them. They figured these things were just extracurricular activities.

Were you interested in poetry because of the proximity of your home to North Beach? Like City Lights bookstore?

Yes. I hung out there as a kid. I was pre-teen. City Lights always intrigued me, especially the basement. There was a big bulletin board that had announcements, bands looking for singers, everything. And it would stir my imagination: “Wow, what if I could do this?” I would go hang out downstairs. They had little cafe tables and chairs. Just take stuff off the shelves and read.

I was reading a lot in the Buddhist sections, Zen and poetry and plays. I think that’s why I got into theatre arts. The poetry I didn’t understand. [But] the cadence, the rhythms, the rebelliousness and the tone of defiance really attracted me.

You also enjoyed rock music. You joined a band called Glass Mountain.

The guy that started the band was a former IBM engineer, so he built all the equipment. He was brilliant, but he dropped out.

When did you begin to shape your social activism?

Of course you were surrounded by activism at SF State. Did you get involved? Oh, yes. I marched against the Vietnam War and participated in a lot and even marched against the Chinese Six Companies. [Laughs.] I think being a Chinese American with parents who clearly had been discriminated against, that many incidents that I witnessed shaped my view about the lack of equality in our system and the treatment of people of color

Your activism, your concern for people, have come out in many different forms, whether it’s books, like “Island,” with the poetry of Asian detainees on Angel Island, carved into walls, or a documentary about your language barrier with your mom, “The Only Language She Knows,” and poetry of your own, in “Winter Place,” the Chinatown alley where your childhood home was … or your plays, including “Paper Angels,” set on Angel Island “XX,” about women.

That (“XX”) was one big boost to my self-confidence, winning the SFSU Playwriting Award. It was judged by Ntozake Shange, the author of “For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When the Rainbow Is Enuf.”

And now, you are poet laureate of San Francisco. Yay! [Chuckles.] How do you feel Asian Americans have fared over the 50 or so years since you began to write and perform? Are there now more open doors, open stages, open hearts?

Yes. I think I was one of the first ones at the gate, to kick down a lot of those doors. It’s really inspiring to see how many young folks have come forward in almost every creative field and been able to reach pretty high level of attainment in their fields, whether it’s in theatre or in music, poetry or fiction.

You also taught for many years, including creative writing at the New College [of California]. Did or do you enjoy teaching?

I do, and I think that I’m still the teacher. Whatever medium, I’m still teaching.

Features

Room to Grow

SFSU a commuter school? Not for the thousands of students thriving together in modern on-campus housing.

Cover Stories

To celebrate the magazine’s 25th anniversary, check out our favorite covers since our founding at the turn of the century.